10. The Modern Movement Comes South

An article about synagogues by Bruno Funaro in the November 1939 issue of Architectural Record was prophetic in its last lines: “A still further step in synagogue design will be attained when the architect . . . is able to use as his means of expression the essential architectural qualities of the structure and free himself entirely of literary and stylistic decoration.”1 At the same time, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, congregational financial constraints—similar to those described in section 9 for Covington, Kentucky—dovetailed nicely with the austere aesthetic aims of the young modernist Louis Kahn, who designed two functionalist Orthodox synagogues during the Depression.

Greek-born Jewish architect Raphael Soriano’s Latz Memorial Jewish Community Center in Los Angeles, constructed in 1939, is possibly the first American Jewish communal building conceived in the International style.2 The primary characteristics of the style are “rectilinear forms; light, taut plane surfaces that have been completely stripped of applied ornamentation and decoration; open interior spaces; and a visually weightless quality engendered by the use of cantilever construction. Glass and steel, in combination with usually less visible reinforced concrete, are the characteristic materials of construction.”3

Both Kahn and Soriano’s work coincided with the arrival in America of a wave of prominent Jewish modern architects fleeing the Nazi regime—but these architects would not produce work in the United States until after World War II. In any case, the national changes did not reverberate across the South until the 1960s. Only a few southern architects, such as Samuel Wiener Sr. of Shreveport, Louisiana, fully embraced modernism before 1945.

In post–World War II America, for a variety of reasons—historical, religious, economic, and aesthetic—most synagogue building committees were willing to take Funaro’s “further step,” to free themselves entirely of “literary and stylistic decoration,” though they did often hang onto symbolism.

Following the Second World War, Jewish communities across the South were dramatically transformed, mirroring national trends. Social and demographic changes had three fundamental effects on Jewish settlement patterns, and by extension, on the use of old synagogues and the construction of new ones.

First, as in much of America, postwar southerners took advantage of new material wealth to expand beyond city boundaries and create new suburbs. Part of the centrifugal impulse can be attributed to “white flight”—the migration of white residents from downtown neighborhoods to new racially restricted housing developments. Many Jewish congregations followed leading members to locations on the outskirts of cities. Changing demographics combined with preferences for modern styles and new forms of synagogue organization led to a boom in synagogue construction in the 1950s and ’60s.

In cities such as Washington, D.C., Baltimore, Maryland, and Charlotte, North Carolina, and even smaller communities like Pine Bluff, Arkansas, congregations moved further away from their urban roots, and built new structures in more spacious neighborhoods. Some remained urban, connected by public transportation, but most embraced the suburban ethos and developed campuses on large tracts of land. In larger cities like Atlanta, Houston, Dallas, St. Louis, and Baltimore that sprawled along new highways in the postwar era, many congregations abandoned prewar buildings and built anew. In Baltimore, Baltimore Hebrew, Oheb Shalom, and Chizuk Amuno, which are pictured in this exhibition, are examples of this trend.

Still, the southern urban exodus was slower and smaller than in the North. Consequently, some older congregations stayed in their historic locations and remained active—notably in Charleston, South Carolina; Savannah, Georgia; Birmingham, Alabama; and Norfolk, Virginia. Many of these synagogues are now revered as historic monuments, and in the late 20th century new wings have been added with more modern amenities, which also often include expanded exhibition spaces.

Synagogues—whether in old neighborhoods or new—were no longer the physical centers of Jewish community. In general, southern Jews participated widely in broad-based community organizations and institutions, and often specifically Jewish activities centered around local Jewish community centers, which served Jews from multiple congregations, and many non-Jews, too. Synagogues had to adapt and strive to be relevant as centers of Jewish cultural identity and activity for far-flung congregants.

Second, while many small-town Jewish communities peaked briefly after the war, they then resumed a population decline that had begun two decades before, after the First World War. Young people went off to war or departed for college and big cities for education and work. In many localities this led to the merger of congregations, and in some, the closure and sale of synagogues.

Third, although suburbanization began and affected older cities in the North first, with the advent of air conditioning, many northerners began to move south. The flight of manufacturing industries from the unionized North to the “right-to-work” South stimulated further southern migration. Suburbs grew in Florida, Texas, South Carolina, Georgia, and elsewhere. Within the region, working-age Jews have migrated, like other southerners, to major cities like Washington, D.C., the Raleigh-Durham area, and Charlotte, North Carolina, and metropolitan Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, and Miami. This migration continues today, with new centers of attraction for young people like Austin and San Antonio, Texas, and New Orleans, Louisiana, while Jewish retirees now no longer go just to Florida but settle across the South. Sometimes these newcomers have invigorated older southern communities, but sometimes they have merely transplanted northern sensibilities—and even northern architects—to warmer climes.

The newest trend in southern Jewish communities, begun in Charlotte, North Carolina, in the 1980s with the opening of the 54-acre campus of Shalom Park, is the consolidation of almost all Jewish communal, educational, and religious institutions on one suburban campus. While this arrangement offers efficiencies and security, as well as greater mingling of all constituencies in the Jewish community, it also enforces Jewish isolation and even segregation from the greater community—reversing more than a century of social development where synagogues were integrated into the urban environment and Jews and Christians rubbed elbows in daily encounters. Charlotte’s Shalom Park was the direct inspiration for the Dell Jewish Campus in Austin, Texas, founded in the mid-1990s.

Migration and, in some places, community expansion have provided occasions for congregations to build—and since the 1950s they have increasingly turned to Jewish architects to design new synagogues. Synagogues of the South includes modern works by nationally prominent Jewish architects Percival Goodman, Sidney Eisenshtat, Sigmund Braverman, and Morris Lapidus, and the lesser known but notable Lenard Gabert, Sheldon Leavitt, and Daniel Schwartzman (1908–1977), who in the mid-1950s designed the fourth home of Congregation Chizuk Amuno in Baltimore. While some designers of modern synagogues in the South were northerners, many were southern-born, and some were congregants.

Southern Jewish architects include, among others, Max J. Heinberg (1906–1982), who designed Gemiluth Chassodim Synagogue in Alexandria, Louisiana; Lenard Gabert (1904–1977), who drew plans for Congregation Emanu El in Houston; Louis Wolff (1910–1977), who designed Tree of Life Synagogue in Columbia, South Carolina; and Sheldon Leavitt of Norfolk, architect of many synagogues in Virginia, as well as in North Carolina and Ohio. Benjamin Hirsch (1932–2018), architect of Synagogue Emanu-El in Charleston, South Carolina, came to Georgia after escaping Nazi Germany as a child on a Kindertransport. As an adult he established a successful architectural practice in Atlanta, where he designed a Memorial to the Six Million and several synagogues. 4

An influential Jewish modernist who did not, however, design synagogues, was the previously mentioned Samuel Weiner Sr. (1896–1977) of Shreveport, Louisiana. Notable non-Jewish architects engaged by southern congregations include Walter Gropius, who worked with Leavitt on the design of Oheb Shalom in Baltimore, and William Wurster, consulting architect for Temple Emanu-El in Dallas.

Though the pace of synagogue construction has slowed, in the 21st century, important new structures are being built. Austin, Texas is one of the fastest growing Jewish centers of the South. Computer entrepreneur Michael Dell helped found the Jewish Community Dell campus there in the mid-1990s, on which two notable modern synagogues have been erected, and to which the 1893 Orthodox synagogue of Brenham, Texas, was moved in 2014. No doubt, the appearance of synagogues and the public face of Judaism in the South will continue to change as this century progresses.

What will the architecture of a sanctuary mean to the people who pray there, and what will the synagogue’s appearance say to folks on the outside – if the building is visible to the broader public at all? Will new synagogues reflect any traditional behaviors and values unique to the South? Or have regional variations in Jewish communities – and any local references in the architecture of their synagogues – been largely erased by the peripatetic nature of American Jews? Will the unity in synagogue design that is a result of the 20th-century triumph of modernism as an architectural style continue, or will the next generation of builders be less conformist and strive for new variations? New forms of Jewish communal organization and new congregational preferences in liturgy already are requiring new and innovative uses of access, technology, space, and decoration. How will this impact future synagogue design?

History suggests that synagogue architecture will not stay constant but will respond to changing times and continue to evoke the congregation’s aspirations and anxieties through their built environment.

1 Bruno Funaro, “American Synagogue Design: 1729–1939,” Architectural Record 86 (November 1939): 65.

2 First named in 1932 by Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson in their International Style: Architecture Since 1922, which served as a catalog for an architectural exhibition held at the Museum of Modern Art.

3 “International Style,” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/art/International-Style-architecture.

4 On Hirsch’s life and career see his obituary: https://www.atlantajewishtimes.com/obituary-benjamin-hirsch/.

Houston, TX ~ Congregation Emanu El (1949)

Tulsa, OK ~ Temple Israel (1955)

Petersburg, VA ~ Brith Achim (1955)

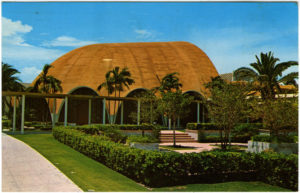

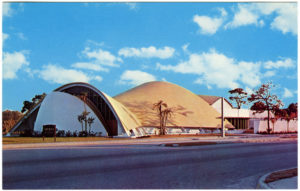

Miami Beach, FL ~ Temple Beth Sholom (1956)

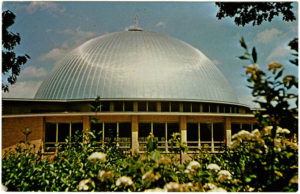

Pikesville (Baltimore), MD ~ Chizuk Amuno Congregation (1955)

Columbus, GA ~ Temple Israel (1958)

Tampa, FL ~ Congregation Schaarai Zedek (1958)

Baltimore, MD ~ Har Sinai Congregation (1959)

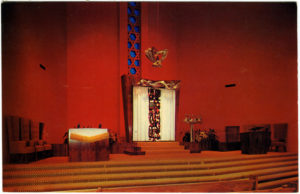

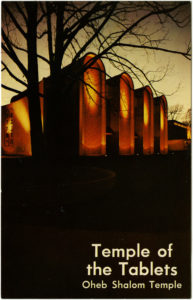

Pikesville (Baltimore), MD ~ Temple Oheb Shalom (1960)

St. Petersburg, FL ~ Temple Beth-El (1961)

Creve Coeur (St. Louis), MO ~ Congregation Temple Israel (1962)

El Paso, TX ~ Temple Mount Sinai (1962)

Miami Beach, FL ~ Beth Israel Congregation (ca. 1965)

Miami Beach, FL ~ Temple Beth Raphael (1966)