4. Moorish Style

The Moorish style was first used for American synagogues just after the Civil War, with major buildings erected by Reform congregations in Cincinnati and New York. Already in 1864, the inclusion of two bulbous domes atop the twin towers of the German Reform congregation Keneseth Israel in Philadelphia pointed the way.

This was a prosperous period for Jewish communities in northern states, where German-speaking congregants had been settled for a generation. By the 1870s, northern Jews were increasingly prosperous; some saw opportunities in the devastated South and came down to fill economic niches vacated by dislocated southerners. Nationally, the Ashkenazi presence, already strong after the large wave of immigration in the 1840s, was firmly established. Jewish communities from coast to coast, along the Mississippi and other waterways, and west through the cotton belt and Texas, began ambitious building programs. The last quarter of the 19th century was the heyday of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (UAHC), founded in 1873 with the active involvement of southern congregations. The Reform Movement did not yet have to cope with the transformation of American Judaism (and the growing Christian doubts of whether Jews could be good Americans) it would soon confront with the mass migration of Orthodox and mostly poor Eastern European Jews to American shores.

Following the Civil War, tastemakers looked to European Jewish centers for the newest religious and cultural trends. They imported Reform rabbis and innovative ideas about synagogue architecture. The rise of the “cathedral synagogue,” typically a large and lavish structure in European city centers, provided ambitious Americans an example to emulate. Pictures and descriptions of new buildings in Vienna, Berlin, and Budapest offered concepts and models for American patrons and architects.1 The Moorish style, also called Oriental, clearly did not derive from Sephardic Spain, but from Ashkenazic Central Europe. In an 1864 issue of the Israelite, a letter from Germany connects European developments and American designs: “You probably know, that in Berlin Jews are building a large and magnificent synagogue which will be ranked among the most splendid edifices.”2 Only later, with the distribution of writings of German Jewish historian Heinrich Graetz celebrating the “Spanish Golden Age,” were Moorish synagogues explicitly linked with medieval Jewish history.

The style was not entirely unknown in America. Variants of Oriental motifs were familiar in country houses of the artistic elite and in recreational and public contexts: amusement parks, fairs, expositions, and railroad stations. P. T. Barnum built Iranistan, a fantastic pleasure pavilion near Bridgeport, Connecticut, in 1848. Significantly, he engaged Jewish-immigrant architect Leopold Eidlitz. In 1852, Samuel Sloan illustrated an “Oriental Villa” in his influential Model Architect, establishing the Oriental as an alternative to Gothic, Norman, and other styles. In 1853, the wildly popular Crystal Palace was erected in New York for the World’s Fair, with dome, minarets, and arabesque parapets. Then, 20 years after Iranistan, Eidlitz and fellow Jewish-immigrant architect Henry Fernbach amazed the country with their new Temple Emanuel in New York, which adapted the Moorish style for synagogue architecture and incorporated materials and building techniques introduced at the Crystal Palace.

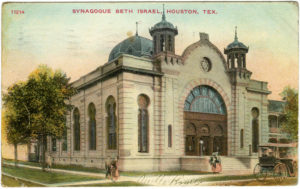

After the Civil War, congregations in San Francisco, Cincinnati, New York, and St. Louis built monumental synagogues incorporating Moorish horseshoe arches and elaborate bulbous and ornamented cupolas on towers and domes. In St. Louis, Congregation Shaare Emeth dedicated an impressive two-tower structure in 1869. Many examples of the Moorish style—often mixing Gothic elements—followed in Galveston (B’nai Israel, 1870) and Houston, Texas (Beth Israel, 1874); Macon, Georgia (Beth Israel, 1876), and Atlanta (Hebrew Benevolent, 1877); Baltimore, Maryland (Chizuk Amuno, 1876); and Nashville, Tennessee (Ohavai Sholom, 1876). According to historian Michael Meyer, Moorish synagogues seemed to proclaim “that political and cultural integration did not require abdication of origins.”3

The American Israelite reported on Atlanta’s temple dedication in 1877, using perhaps for the first time the term “Moorish” to describe a southern synagogue:

an ornament to the city and a monument to the congregation…. It is built of brick with stone trimmings, and is one of the most substantial edifices in the city…. The architecture is Moorish and the design is that of Mr. W. H. Parkins… [The] exterior of the building is decidedly unique, and will attract attention at once. Its proportions are quite harmonious and it has an appearance both of solidity and grace well mingled.4

The taste for Moorish style continued through the 1880s. In Kansas City, Congregation B’nai Jehudah dedicated an impressive new Moorish synagogue in 1885. Rabbi Isaac Wise, head of the Reform Movement, spoke at the dedication. The Fair Journal previewed the building in November 1884:

It is the only representation of the Moorish style of architecture in this city, and for its faithful copy and its excellent execution and finish, its architect, Mr. H. Probst, has gained for himself a deserved reputation. Like the faith of Israel, the temple rests upon solid rock. Its basement is massive white limestone, all above ground, will stand the gnawing tooth of time and the inclemencies of the seasons for many centuries ere it will crumble into dust….”5

The synagogue may have been able to withstand the passing of time, but not the changing of tastes. In 1908, the congregation moved to a new classical-style synagogue and this building was sold.

Despite their displacement by Renaissance and classical-inspired styles, which began in the mid-1890s, Moorish synagogues continued to be built until World War I—for example, Congregation B’nai Brith Jacob (1909) in Savannah, Georgia, and Temple Sinai (1912) in Sumter, South Carolina—by which time Moorish was widely regarded as a true and historic Jewish style. This belief may explain its acceptance and use by Orthodox congregations long after Reform Jews had moved on to more “modern” architectural expressions.

1 For a review of these styles and examples of the most prominent new synagogues, see Carol Herselle Krinsky, The Synagogues of Europe: Architecture, History, Meaning (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1985), passim. For detailed case studies of four European cities, see Saskia Coenen Snyder, Building a Public Judaism: Synagogues and Jewish Identity in Nineteenth-Century Europe (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2013).

2 Henry Vidaver, “A Historical Sketch of the State of Judaism in Berlin since the time of Moses Mendelssohn,” Israelite 10, no. 43 (April 22, 1864): 341.

3 Michael A. Meyer, Response to Modernity: A History of the Reform Movement in Judaism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 183, quoted by Weissbach, 68.

4 “A New Temple,” American Israelite, September 14, 1877, 2.

5 Quoted in Frank J. Adler, Roots in a Moving Stream: The Centennial History of Congregation B’nai Jehudah of Kansas City 1870–1970 (Kansas City, Mo.: The Temple, Congregation B’nai Jehudah, 1972), 61. The article was reprinted in Kansas City Journal (Nov. 19, 1884) and in the American Israelite (Dec. 5, 1884). The Evening Star, Nov. 19, 1884, provided front-page coverage.

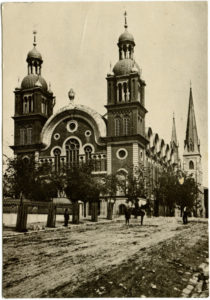

St. Louis, MO ~ Congregation Shaare Emeth (1869)

Nashville, TN ~ Kahl Kadesh Ohavai Sholom (1876)

Port Gibson, MS ~ Temple Gemiluth Chassed (1892)

Wheeling, WV ~ Congregation L’Shem Shomayim/Eoff Street Temple (1892)

El Paso, TX ~ Temple Mount Sinai (1899)

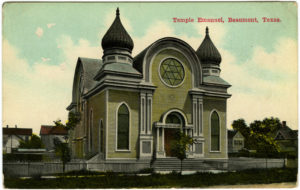

Beaumont, TX ~ Temple Emanuel (1901)

Houston, TX ~ Congregation Adath Yeshurun (1905)

Houston, TX ~ Congregation Adath Yeshurun (1908)