7. The Classical Norm (1910-1940)

7. The Classical Norm (1910-1940)

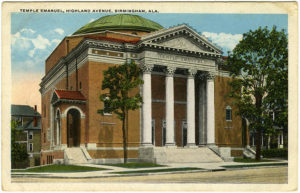

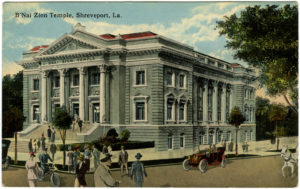

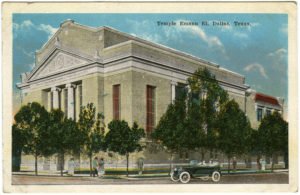

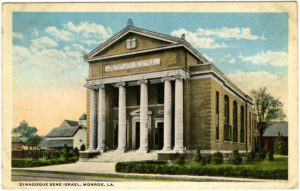

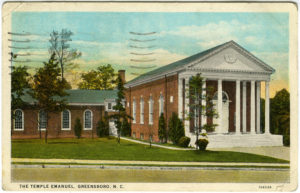

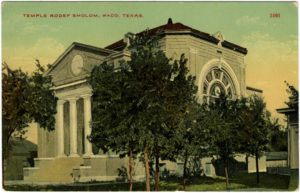

Classicism spread across the South and many Reform congregations, such as Temple Rodef Sholom (1910) in Waco, Texas; B’nai Zion Temple (1914–15) in Shreveport, Louisiana; Temple Emanu-El (1917) in Dallas, Texas; B’nai Israel (Bene Israel) (1917) in Monroe, Louisiana; and Temple B’nai Israel (1917) in Spartanburg, South Carolina, continued to build in the classical style through the years of the First World War. For several succeeding generations, the Jewish synagogue as classical temple became a fixture of southern towns and cities and helped define popular perceptions of Jewish identity. Design changes came not so much in architecture style but in the growing list of technological innovations and additions. Some of these were structural, with increased use of steel framing to allow bigger roof spans and larger open sanctuaries, and the incorporation of “fireproof” brick and asbestos roof tiles. But many technological changes were designed to permit greater utility and comfort of interior spaces, with the hope that the improvements would encourage more frequent use of the building.

Changes included installation of electric lights, microphones for vocal amplification, improved ventilation systems for air circulation and cooling, more modern kitchens with new appliances, and better and bigger restrooms for men and women. In addition, most new synagogue plans emphasized ancillary spaces beyond the sanctuary. Ample social halls for dinners and dances with kitchens and coatrooms to serve them were common, and more appealing office and classroom spaces were included in new designs. Architects began to design flexible spaces with sliding and accordion doors to configure for educational and social activities as needed.

These new amenities can sometimes be seen or intuited in the architecture—even in the views shown on postcards. The simple geometry of the classical block was often extended to provide more space, and sanctuaries are frequently built freestanding on high platforms to create imposing structures, and also to maximize natural light to the sanctuary and to basements where the walls were lit by above-ground windows.

A few of these buildings are still in use today, but in smaller towns where Jewish communities have dwindled or disappeared entirely, and in larger cities where congregations have moved to new neighborhoods, many pre–World War II buildings have been sold for other uses or demolished entirely (see section 10). While some classical synagogues built in the South in the early 20th century remain Jewish houses of worship—notably those in Natchez, Mississippi; Richmond and Norfolk, Virginia—of the synagogues shown in postcards in this section, only Temple Emanu-El in Birmingham, Alabama, is still used for its original purpose. Others are used churches and some have been torn down.

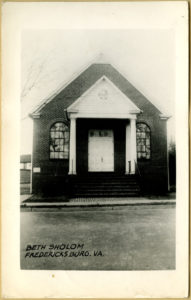

Just as the Moorish style adopted by many Reform congregations in the mid-19th century was embraced by Orthodox congregations a generation later, so too did classicism spread from the Reform Movement to other branches of Judaism, including traditional (Orthodox) Judaism and the nascent Conservative Movement. After 1901, and especially after World War I, Conservative Judaism spread across the United States as an adaptation of Orthodoxy to modern American conditions—an adaptation that initially was more about style and synagogue organization than about theology, interpretation of Jewish law, or liturgical practice. As such, the Conservative Movement began to establish congregations in the South in the interwar period and set itself up as an acceptable modern alternative to Reform Judaism. Conservative Judaism became the primary road to modernization and acculturation of the first American-born generation of Eastern European Jews, in the same way that the Reform Movement had encouraged the Americanization of German-speaking Jews in the 19th century.

Nationally, new Conservative congregations (and some Orthodox ones as well) championed the classical style in the interwar years, especially with the creation of synagogue centers in large cities in the 1920s, but this development mostly bypassed the South.