6. The Classical Moment (1900–1910)

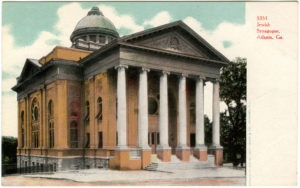

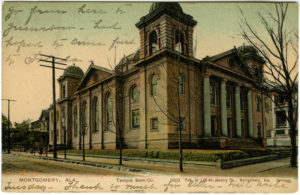

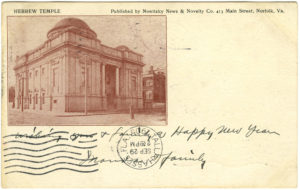

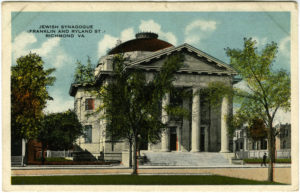

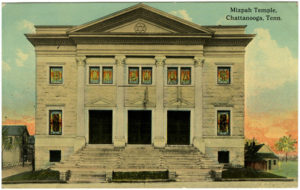

During the first decade of the 20th century, classically inspired Reform temples were erected in towns and cities in almost every southern state. The boom began with the opening of new synagogues for Hebrew Benevolent Congregation in Atlanta and Beth Israel in Macon, Georgia; Ohef Sholom in Norfolk, Virginia; and Temple Beth Or in Montgomery, Alabama; followed by the dedications of Beth Ahabah in Richmond, Virginia, and Mizpah Congregation in Chattanooga in 1904.

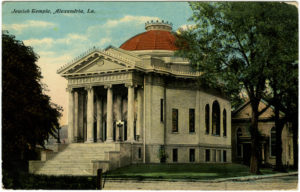

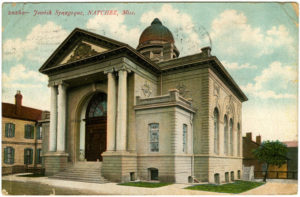

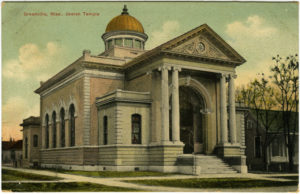

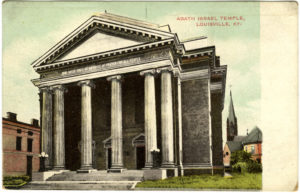

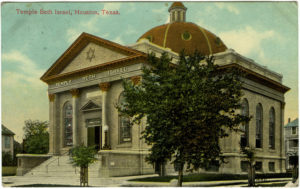

An incomplete list includes Temple Adath Israel (1906), Louisville, Kentucky; Temple Chester B’nai Sholem (1908), New Bern, North Carolina; Beth Israel (1908), Houston, Texas; Congregation Gemiluth Chassodim (1908), in Alexandria, Louisiana; Temple B’nai Israel (1908) in Sheffield, Alabama; and three Mississippi synagogues: B’nai Israel (1905), Natchez; Beth Israel (1906), Meridian; and Hebrew Union Congregation (1906), Greenville. The popularity of the classical style for Reform temples continued into the next decade, but except for larger structures and more ornate stained glass, there were few new creative or functional innovations (see Section 8).

Most of these temples—to use the term preferred by their benefactors and builders—were prominently located on important streets, sometimes downtown, but often in newly developed still verdant neighborhoods. Their imposing architecture fully engaged the cities in which they stood. They were built to serve Jews, but they were also public monuments, and architecturally spoke as part of a civic discourse about religion, pluralism, democracy, beauty, and civic responsibility. To Jews and Christians of a century ago, architecture mattered.

From the late 1890s until the First World War, thousands of white (and gray) buildings with columns, pediments, and domes were erected across America. Classicism was tied to civic life through the architecture of libraries, courthouses, post offices, universities, and banks. In the early 19th century the Greek Revival style, as employed at K.K. Beth Elohim in Charleston, South Carolina, had helped define the values of the early republic. Now, a full-bodied Roman classicism reflected the aspirations of the new American empire. The Reform Movement especially found the new classical style an appropriate language for the upcoming generation of 20th-century Reform temples. Synagogues that superficially resembled Roman temples began to be built across the country, especially in the South, where the Reform Movement was strong and its congregations stable and prosperous.

In 1905, three “modern classic” temples (with a general similarity to recently erected domed synagogues in Detroit and Richmond) were dedicated in Mississippi—in Meridian, Natchez, and Greenville. Similar buildings were soon designed for Beth Israel in Houston, Texas, Congregation Gemiluth Chassodim in Alexandria, Louisiana, and Temple Emanu-El in Birmingham, Alabama. Each temple had unique features, but these were variants on a quickly accepted form. Beth El in Houston, for instance, did not have an open portico, but rather a closed wall with two applied columns and two applied corner pilasters, between which were two large round-arched windows and a central entranceway surmounted by a classical pediment, in which was inscribed an identifying Jewish star. Unlike at Richmond’s Beth Ahabah, the architect chose the softer Corinthian order, included only one doorway at the top of the approach steps, and preferred round arches over flat Doric style lintels.

Classicism was a language accepted and understood in the South, where it had a very different association than in the North and East. The architectural language was ordered, clear, and dignified but it could also be interpreted in different ways. In the North, Greek classicism in both public and private buildings had been associated with democracy and the early republic. By mid-century, however, its clarity of purpose was increasingly replaced with English-inspired Gothic and, after the Civil War, with increasingly ornate variations. In the South, too, public buildings—including those designed by Thomas Jefferson—were often conceived in the classical style, as were plantation houses of the wealthy elite.

In the 1890s and early 1900s, following the success of the Roman-inspired “White City” of the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, a new variety of classicism in New York, Cleveland, and other northern cities was embraced by advocates of the City Beautiful Movement, many of whom were also social reformers combatting urban corruption and the plight of poor immigrants. But in the South, classicism evoked the antebellum period, a period of sharp class and race distinctions rooted in slavery. In the South, classicism associated Reform congregations with a national religious movement, but it also provided unexpected connection to the regional past.

While most architects of southern classical temples appear to have been Christian, classicism was not a style imposed upon Jewish congregations by Christian architects. American classical synagogues emerged within the American Jewish community as a way of presenting—and even controlling—communal identity. As art historian Martin Powers has written, “What we call ‘style’ is an important means whereby social groups project their constructed identities and stake their claims in the world.”1

The acceptance of classicism was also an explicit rejection of exoticism, otherness, and the widespread perception, sometimes self-presented, of Jews as “Oriental.” American Jews—especially Reform Jews—wanted nothing of that. According to Leo Wise, son of Rabbi Isaac M. Wise and longtime editor of the American Israelite, “American Jews are differentiated from American Christians in religion only, not in nationality, and there is no such thing today as a Jewish nation.” 2

Contemporary European imperialism in the Near East cast “Orientalism” as a decadent, subjugated tradition, while in the United States the term “Oriental”, besides referring to Chinese and Japanese immigrants, was commonly applied to the new waves of so-called Russian, Yiddish-speaking Orthodox Jews from Eastern Europe. Escalating Eastern European Jewish immigration was threatening to many already-Americanized Jews, as it was one factor blamed for rising public expressions of anti-Semitism, which reached a level not previously experienced in this country. The classical-style temple placed the Jews firmly in the western cultural world and in the American civic-minded present day. In the South, classicism could also signal rootedness in local white Protestant traditions, and even suggest parity with Christian churches.

1 Martin Powers, “Art and History: Exploring the Counterchange Condition,” Art Bulletin 77 (September 1995): 384.

2 Leo Wise quoted in “American Israelite,” in Jewish Encyclopedia 1 (New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1901): 518–19.

Atlanta, GA ~ Hebrew Benevolent Congregation (1902)

Montgomery, AL ~ Temple Beth Or (1902)

San Antonio, TX ~ Temple Beth-El (1902)

Norfolk, VA ~ Ohef Sholom (1902)

Richmond, VA ~ Beth Ahabah (1904)

Chattanooga, TN ~ Mizpah Congregation (1904)

Natchez, MS ~ B’nai Israel (1905)

Greenville, MS ~ Hebrew Union Congregation (1906)

Meridian, MS ~ Beth Israel (1906)

Louisville, KY ~ Temple Adath Israel (1906)

Oklahoma City, OK ~ Temple B’nai Israel (1908)

Kansas City, MO ~ Congregation B’nai Jehudah (1908)

Houston, TX ~ Beth Israel (1908)