9. Art Deco, Moderne, and International Styles

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, when few new synagogues were built in the United States, it wasn’t clear that southern Jews, who continued to work hard to look and act like other Americans, would embrace modernism of any sort for synagogue architecture. Even ornate variations of the Art Deco style with its clear geometries, flat walls, and crisp relief ornament would have appeared radically different from the churches, schools, and courthouses that synagogue builders often emulated. With few exceptions the last big synagogue buildings erected before the Depression were an eclectic mix of historicist forms.

Modern styles—that is, styles that were neither historicist nor traditional—also had functionalist roots in American industrial architecture, and newer forms had been grafted on during the interwar period. American Jews played a major role in the development and promotion of Art Deco and Art Moderne designs, especially in New York, where Jewish architects and developers such Ely Jacques Kahn, Irwin S. Chanin, and Abe N. Adelson were practitioners and proponents of the styles for tall urban office and apartment buildings.

A small number of Deco and Moderne synagogues and other Jewish institutional buildings of the late 1920s, and a few in the early 1930s, pointed in the direction of what would become an almost total embrace of new modern styles by Jewish builders after World War II. Outside of the South, the stripped-down Byzantine style of Temple Tifereth Israel (1923) in Cleveland, Ohio, or the ornate Art Deco style of Temple Emanu-El (1929) in Paterson, New Jersey, were conscious aesthetic choices; both buildings were exceptionally costly to construct.

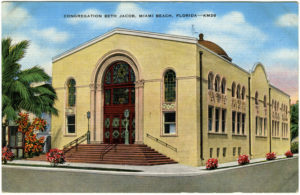

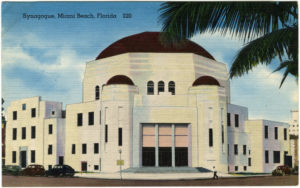

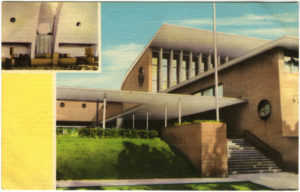

The Art Moderne style was widely featured in 1930s escapist movies (think Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers RKO musicals); and both Art Deco and Moderne were often associated with commercial and recreational architecture, such as for expositions and fairs, and especially coastal resorts. Not surprisingly then, it was in Miami Beach that the new styles first caught on in synagogue design, beginning with H. Fraser Rose’s Beth Jacob (1929), a transitional building that adapts Romanesque and Byzantine decor to a sparer Art Deco form. The shift continued in Miami with Temple Israel, a Gothic-Deco mix built in 1935, and a 1936 addition to Beth Jacob. Modernism emerged again after World War II with the grand Temple Emanu-El (1948) in Miami Beach. This was the last synagogue built by interwar designer Charles Greco, whose Tifereth Israel in Cleveland helped usher in the style. Percival Goodman designed Miami’s Temple Beth Sholom (1956), continuing the trend but incorporating expressive forms over a rational organizing plan.

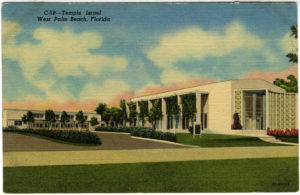

Modern synagogues also were constructed in Hollywood and West Palm Beach, Florida, and elsewhere across the state. Most of these buildings have been demolished or entirely altered, and there are postcards of only a few of them. For the most part, this episode in modern synagogue design remains poorly documented.

A move toward a more austere, spare style fulfilled financial as much as aesthetic purposes. In Kentucky, Agudath Achim (1930s) in Ashland had to be rebuilt after the previous synagogue was demolished to make room for a new post office. The 1939 building is a lean, functionalist structure. Only round-headed sanctuary windows separated by raised vertical strips (like vestigial applied pilasters) on the building flanks suggest that the simple form derives from more ornate historicist Romanesque- or Renaissance-style predecessors. Temple of Israel (1939) in Covington, Kentucky, is similarly simple in design.1 Clearly, economy in scale and materials was important. As the country began to emerge from the Great Depression in the late 1930s, this type of religious functionalism increasingly became the style of choice rather than necessity for new synagogues.

The acceptance of modernist architecture by post–World War II Jewish congregations can be attributed to several factors, one of which was surely the California residential work of European Jewish architects such as Richard Neutra, Rudolph Schindler, and Raphael Soriano in the 1920s and ’30s. In Shreveport, Louisiana, Samuel Wiener Sr. was an early proponent of the Art Moderne style; many of his houses from the 1930s and ’40s are now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Though he was active in the local Jewish community, he did not design synagogues. His residential architecture, however, demonstrated the willingness of individual Jewish clients to embrace modernism. After World War II, congregations building new suburban houses of worship would follow suit.

1 Lee Shai Weissbach, Synagogues of Kentucky: Architecture and History (Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky, 1995), 80.