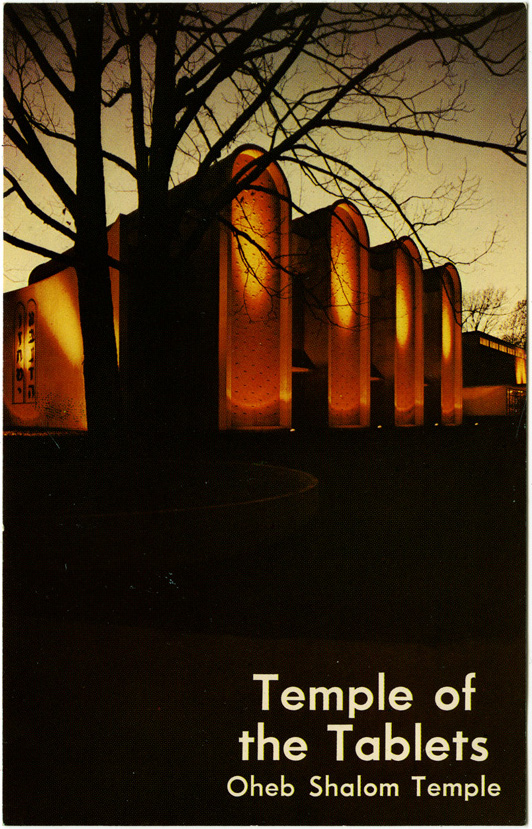

10.9 Pikesville (Baltimore), Maryland

Temple Oheb Shalom, 7310 Park Heights Avenue

Walter Gropius and Sheldon Leavitt, architects, 1960

Mirro-Krome Card by H. S. Crocker Co., Baltimore, Maryland, publisher; no date

Established in 1853, Temple Oheb Shalom (Lovers of Peace) was originally located in South Baltimore. When the Jewish population moved northwest, the congregation relocated to its second home, which became known as Eutaw Place Temple. During the congregation’s centennial year, 1953, it acquired a suburban site and, in 1960, completed the move to Park Heights Avenue. Walter Gropius (1883–1969), in collaboration with Sheldon I. Leavitt, designed the building.

Like Eric Mendelsohn, Gropius came from Germany, but he was neither Jewish nor a refugee. As chairman of the Department of Architecture at Harvard University after 1938, Gropius infused the American architectural mainstream with his passion for modernism. His influence led directly to the eclipse of the Beaux-Arts style in the United States after World War II. Gropius had no prior experience designing synagogues, and there was little in his past that suggested an affinity with sacred space. His plan for Oheb Shalom utilized others’ recent synagogue center innovations, and his design, which has now been substantially altered, looked toward industrial architecture for inspiration.

It was apparently the idea of architect Sheldon Leavitt, whom the congregation had originally consulted, to add Gropius to the design team, in part to help fund raising. Leavitt, who had already designed several synagogues, was ultimately responsible for most of the planning and details of Oheb Shalom, but it was Gropius who created the central idea of the sanctuary space and its formal articulation, sketching out the concept in a single meeting at his Cambridge, Massachusetts, office.

Gropius’s Oheb Shalom conformed to spatial concepts popular at large, new suburban synagogues in the 1950s and 1960s. This was likely due to Leavitt’s input. The plan linked sanctuary, social hall, meeting rooms, administrative offices, and a classroom wing in one connected facility. A central south-north spine ran from a projecting entrance porch, through a long lobby/vestibule, past a small courtyard, through an office wing, and then to the almost detached school area. The worship space was given primacy on the campus. It is the largest element in mass, the tallest in height, the most articulated in form, and almost the first space one encounters when entering. The sanctuary roof is a series of 15-foot-diameter vaults without any interior supports.

The most prominent element in Gropius’s design, repeated within and without the synagogue, is the decalogue—the tall, arched stone tablet upon which the Ten Commandments are traditionally depicted, representing the laws given by God to the Jewish people through Moses on Mount Sinai. On the synagogue’s exterior there is an explicit representation of the Decalogue (Tablets of the Law) on the east wall. Inside, the sanctuary consists of a series of barrel-vaulted sections aligned to create a sequence of seven bays looking like single wings of the typical Decalogue tablet.

Lighting in the sanctuary was intentionally subdued to create, in the words of Leavitt, “the mood of the sanctuary as one of reverence.” There were few windows in the building, but skylights were placed to light the ark. Now that the ark has been moved to the opposite end of the space, they provide general, ambient lighting. A stained glass clerestory spanned the rear wall. Now it tops the ark wall and has become a major decorative element.

1 Sheldon Leavitt, in private conversation with Samuel D. Gruber, 2009. Reported in “The Modern Synagogues of Sheldon Leavitt,” Samuel Gruber’s Jewish Art & Monuments, December 9, 2009.