6.10 Louisville, Kentucky

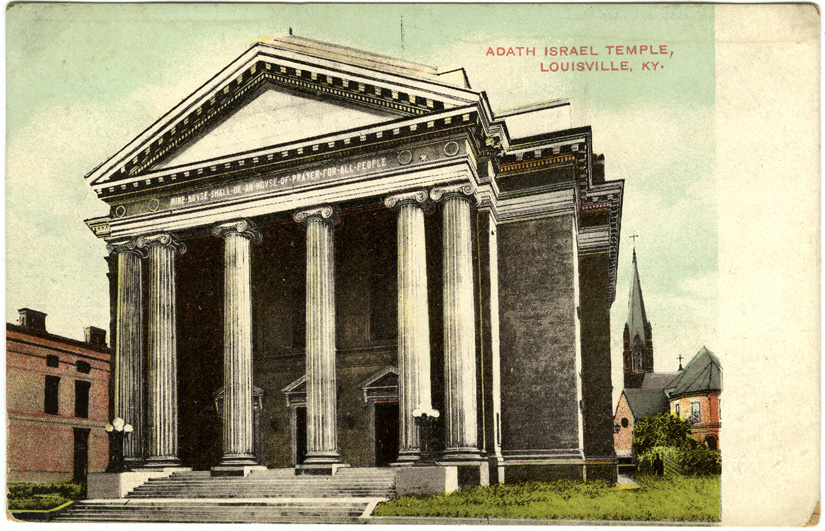

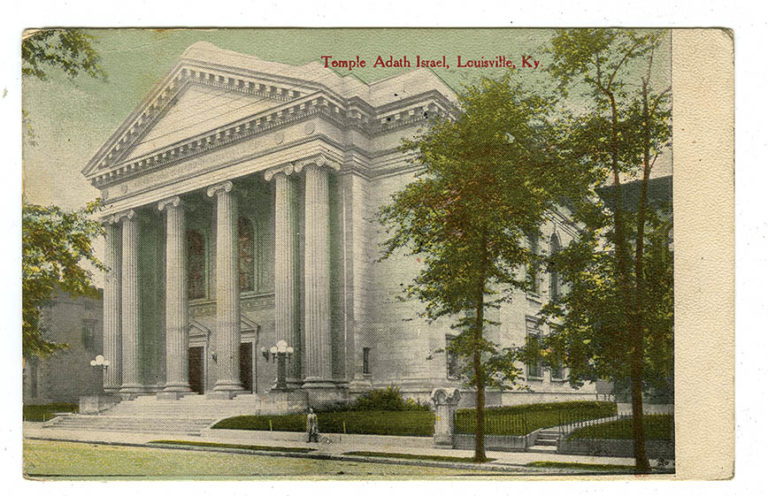

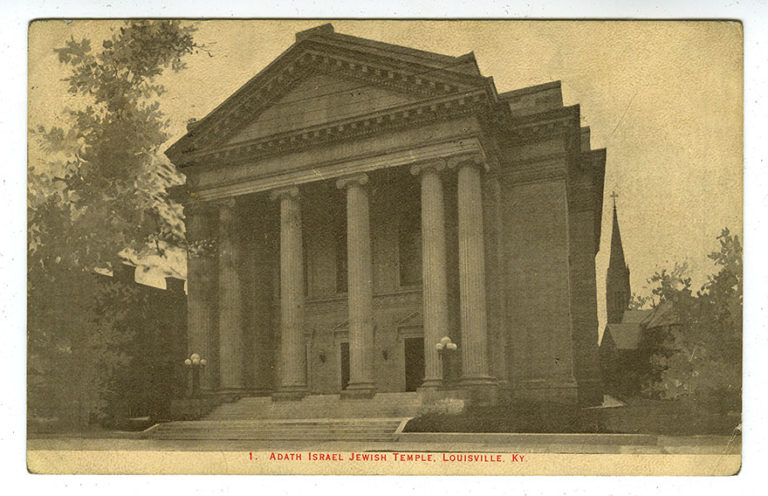

Temple Adath Israel, 834 South 3rd Street

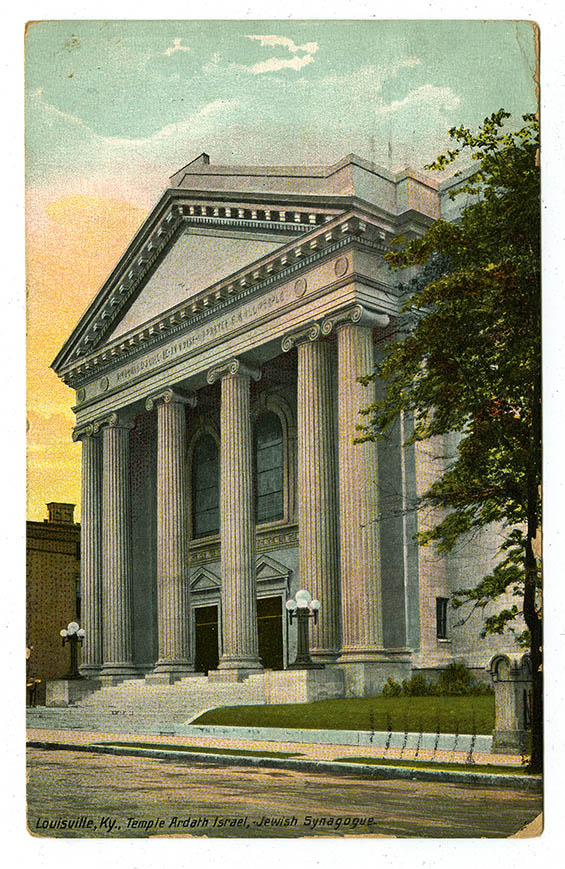

Kenneth McDonald and J. F. Sheblessy, architects, 1906

Columbia Novelty Company, Louisville Kentucky, publisher; no date; also on back: “Printed in Germany.”

These postcards show one of the grandest and most celebrated of the many monumental synagogues built across the South at the beginning of the 20th century. Louisville’s Temple Adath Israel (Congregation Israel) is an excellent example of the ascendancy of the classical style for synagogue architecture among established Reform congregations.

The process for choosing an architect and designing the building also marked a new sense of civic purpose and professionalism among Jewish communities, whose leaders in the early 1900s tended to be businessmen familiar with the latest trends in industrial organization and management.

Adath Israel was designed as a Roman-style temple, with a projecting portico of six fluted Ionic columns supporting a full entablature and large pediment. Across the frieze is written in English an inspirational phrase common on Reform temples: “Mine House Shall be an [sic] House of Prayer for All People.” This ecumenical and inclusive message was at the heart of the Reform Movement’s preference for classical design.

After some stucco work in the earlier temple collapsed in 1904, it was decided to erect a new building. The older synagogue was one of the grandest religious edifices in town and had represented local Jewry since it was erected in 1868. It was a mix of several styles, though its overall expression was that of Gothic ecclesiastical architecture. Any new synagogue would have to make as bold a statement and be as much of a presence in the urban landscape. To that end, the congregation staged a competition for a new design.

Entries were submitted by at least five architects. The project went to Kenneth McDonald and John Francis Sheblessy, prominent local architects and both Christians. According to historian Lee Shai Weissbach, “There is no way of determining whether [the architects] were aware of recent Greco-Roman synagogue discoveries in Palestine.” But they—and the congregation—surely would have known Arnold Brunner’s articles in the contemporary Jewish Encyclopedia, and more importantly his design for New York City’s Shearith Israel.

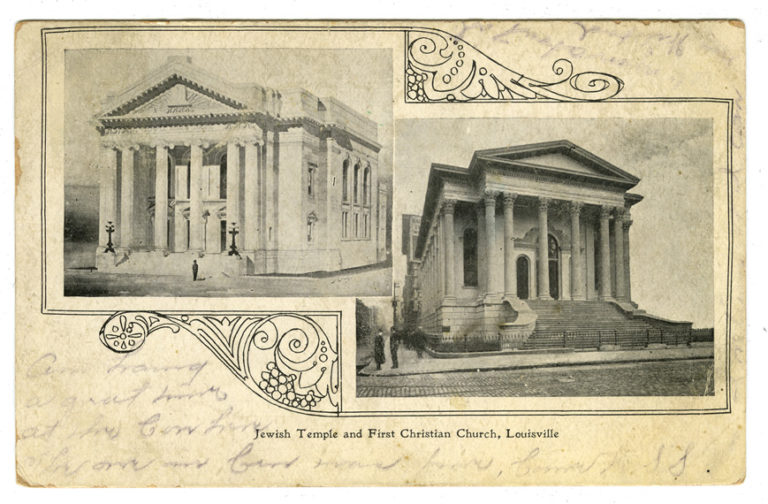

Something of the way Reform Jews saw building classical temples as a strategy for fitting in can be seen in a postcard from Louisville that pairs the new Temple Adath Israel with the First Christian Church. The two buildings are strikingly similar, except that the synagogue image displays a decalogue (Ten Commandments) set within its pediment. As Weissbach points out, however, this decalogue was never installed.