4.1 St. Louis, Missouri

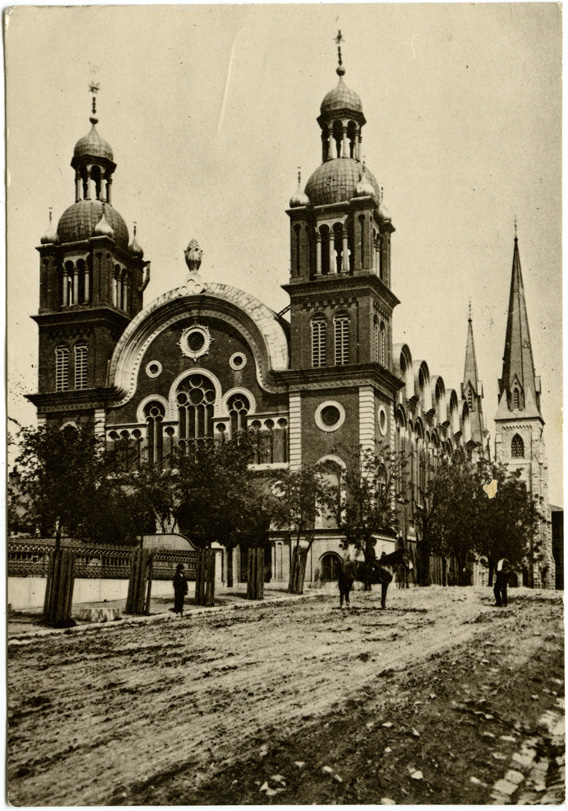

Congregation Shaare Emeth, 17th and Pine streets, as it appeared in 1875

Thomas Brady, architect, 1869

Dover Publications, publisher; 1979

This 19th-century image depicts Congregation Shaare Emeth (Gates of Truth) in St. Louis, Missouri, one of several grand synagogues erected in cities across the South (and throughout the country) in the decade following the Civil War.

The first Shaare Emeth was remarkable for its size and the prominence of its two-tower facade, as well as the bulbous domes and open pavilions that top the towers. The style was eclectic, but it mostly employed accepted elements of Romanesque architecture. It was the horseshoe arches, then becoming popular, that made Shaare Emeth possibly the first “Moorish” synagogue in the border states and the South. Such bold architecture was intended not only for the congregants, but also as an affirmation, for all to see, of Jewish freedom and prosperity.

Despite its pro-slavery and southern sympathies, Missouri was a neutral state, and during the Civil War, St. Louis became a major hub for the Union army and navy. Commercial opportunities attracted Central European Jewish immigrants from parts of the country farther east, and then from Europe itself.

In 1865, as the war ended, 40 members of B’nai El, then an Orthodox congregation, broke off and formed a temple association to build a Reform synagogue. They bought a lot at 17th and Pine for $22,500 and hired architects Thomas Brady and Otto H. Stickel. Construction began in spring 1867, and the cornerstone was laid on June 24. The building, dedicated on August 27, 1869, survived until 1897.

Inside, the sanctuary measured 95 x 65 feet and sat 1,200 people. There were two small aisles and galleries. The barrel-vaulted ceiling rose 50 feet above the floor. Over the entrance perched an organ and choir loft. Twenty-three windows were filled with stained glass, some featuring Jewish religious symbols. The ceiling was painted sky blue and gold, and arabesque tracery in gold and silver filled the walls. Crimson upholstery and plush carpeting added to the sense of opulence.

The size and richness of the new synagogue reflected the prosperity of the city’s Jewish population and their aspirations. But after all, the synagogue had to compete with ever more extravagant social clubs, department stores, and private mansions, let alone large Christian churches.

Shaare Emeth’s congregants worshiped in this beautiful temple for 25 years, after which they relocated to a site west of Grand Avenue.