1.2 Baltimore, Maryland

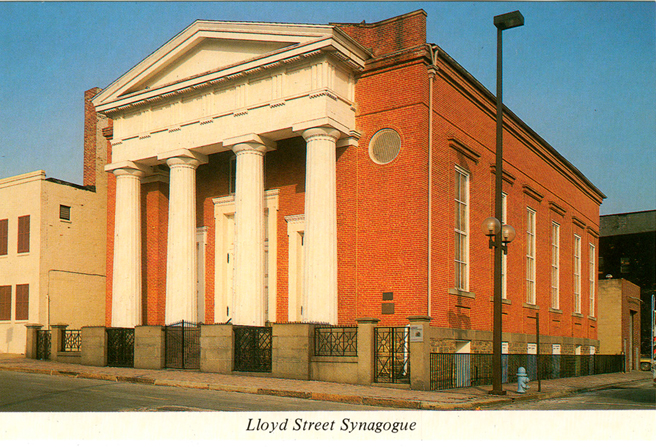

Lloyd Street Synagogue, built for Baltimore Hebrew Congregation, 15 Lloyd Street

Robert Cary Long Jr., architect, 1845; enlarged by William H. Reasin, architect, 1861

D. Traub and Son, Baltimore, Maryland, publisher; no date (postcard obtained by curator shortly after printing, ca. 1990); also on back: “Litho in Hong Kong”

This image shows what the former Baltimore Hebrew Congregation building, or Lloyd Street Synagogue, exterior looked like at one point in time. Since its dedication in 1845, it has served as a house of worship for three different congregations, then as a museum, and has undergone several renovations—a triumph of historic preservation and reinvention. The postcard, as well as an accompanying one of the former Chizuk Amuno Congregation (now B’nai Israel), also on Lloyd Street, were produced to promote these two restored buildings as examples of different 19th-century synagogue styles, and to celebrate an exceptional historic preservation accomplishment.

The Lloyd Street Synagogue was the first synagogue built in Maryland and today is the third oldest standing synagogue in the United States. Over the course of a century, the building provided space for worship, study, and assembly for three different congregations. Baltimore Hebrew Congregation, established by German Jewish immigrants and incorporated in 1830, dedicated the structure on September 26, 1845. Like Charleston’s Beth Elohim, the synagogue’s design reflected the Jewish embrace of Greek Revival architecture, popular across America in the 1830 and 1840s. Almost a national style, classicism was equated with the political as well as the aesthetic values of the still young republic. Though Rabbi Abraham Rice (1800–62), who ministered to Baltimore Hebrew from 1840 to 1849, delivered sermons in German, the building’s appearance would have been considered entirely modern and American. Designed by local architect Robert Cary Long Jr., the synagogue closely resembles his St. Peter the Apostle Church of 1842.

The Lloyd Street Synagogue bears witness to the congregational, liturgical, and architectural changes debated in the mid-19th century as congregations wrestled with new ideas and opportunities presented by the Reform Movement. A description of the building’s dedication by traditionalist Isaac Leeser in the Occident mentions several significant features, including the Doric portico with “a flight of steps on each side” leading up to a gallery that ran on three sides. Leeser wrote that, inside, there was “no platform or Teba (Almemar) but merely a reading desk placed close in front of the Ark. This, a decided defect, is owing doubtlessly to the narrowness of the building, a fault which we fear will not be easily remedied.” The ark (the receptacle where the Torah scrolls are stored), according to Leeser, was “a semi-circle, reached by a flight of steps of the same form, on the plan of the Synagogues of New York.” As regards furnishings: “The usual seats for the officers of the Synagogue consist of two handsome sofas, in perfect keeping with the other arrangements.”1

The 1845 interior was altered 15 years later under the direction of architect William H. Reasin. The building was extended to 30 feet, a new east wall with an ark was erected, and an organ was installed. A full bimah was placed near the new ark, but not immediately in front of it. The sanctuary was remodeled and rededicated again in 1871.

In 1889, the building was sold to St. John the Baptist Roman Catholic Church, one of the first Lithuanian “ethnic” parishes in the United States, whose parishioners worshiped there through 1905. That year it was acquired by Shomrei Mishmeres HaKodesh, an Orthodox Jewish congregation founded by Eastern European immigrants. When the new congregation moved out in the early 1960s, the vacant building was threatened with demolition and the Jewish Museum of Maryland (JMM) was formed to purchase and care for the historic landmark. A restoration was carried out following the standards of the time, removing and replacing some original features. For example, the ark was rebuilt to the wrong size, and the exterior brick was exposed, even though it was never meant to be seen.

In 2008, as part of an ambitious $1 million restoration project, the brick walls were covered with beige stucco, believed to appear more like the building’s original exterior, which was intended to replicate a Greek Revival “temple”—as solid-looking as if it were built entirely of stone.

Avi Decter, JMM’s director from 1998 to 2012, described the changes the Lloyd Street Synagogue underwent through three successive immigrant congregations, from 1845 to 1963. The synagogue’s exterior, he said, “as we see it today is neither accurate nor authentic to any of this landmark’s periods of historical or architectural significance!”

1 Isaac Leeser, “Consecration of the Synagogue at Baltimore,” The Occident and American Jewish Advocate 3, no. 8 (November 1845): 362.