1. Federal Style and Greek Revival

The oldest extant synagogue in the South is Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim in Charleston, South Carolina, dedicated in 1841 to replace a 1794 building destroyed in the great fire of 1838. Beth Elohim, established as a congregation in 1749, built its first sanctuary in the tradition of the so-called Portuguese synagogues of Amsterdam (1680), London (1705), Curaçao (1730), and Newport, Rhode Island (1764).

Charleston’s KKBE received help from its neighbor to the south, Mickve Israel in Savannah, in constructing the region’s first purpose-built synagogue. Abraham de Costa, a wealthy merchant in Savannah, had urged Mickve Israel to build a 45 x 35-foot synagogue with a women’s gallery and offered to purchase all materials and to pay rent on the house where the congregation was meeting until construction was complete. However, congregational disagreements halted progress. By February 1792, de Costa withdrew from the project, claiming that the brick being used was inferior. Just a month later the congregation received a request from Charleston to help with their new synagogue and Jews in Savannah made pledges to the building fund.1

Charleston’s Beth Elohim was a freestanding brick building—essentially a rectangular box with a small narthex and a tall lantern-style steeple rising from its pitched roof. It was well lit with two rows of five windows on each side, a large window in the front of the narthex, and smaller windows on the front of the sanctuary flanking the antechamber. At first glance, it looked like a church, the exterior drawing as much from the English Protestant tradition as from the Jewish.

The inside was more recognizably Jewish. Though destroyed in 1838, the interior is known from a now-famous representation—a view Solomon Nunes Carvalho painted from memory immediately after the fire.2 Following the traditional Sephardic arrangement, benches lined the nave’s sides (set beneath the balconies) and faced the center. The ark was placed against the east wall flanked by two tall windows and surmounted by a fanlight. Two registers of slender Doric columns supported a gallery with a paneled parapet. A wooden barrel vault spanned the nave. The rounded, railed bimah (tevah in Sephardic tradition) was freestanding and near the center of the nave. The arrangement of the seating and the placement of the bimah suggest a compromise between Sephardic and Ashkenazic traditions, reflecting the mixed backgrounds of the congregants.3

Jews of Savannah erected a small wood-frame structure in 1820 as their first purpose-built house of worship. It was destroyed by fire in 1828, rebuilt in brick in 1836, and then replaced in the 1870s with the Gothic-style synagogue in use today.

Jews in Richmond, Virginia, established Kahal Kadosh Beth Shalome in 1789 and worshiped in temporary spaces until a permanent synagogue was dedicated in 1822.4 The structure is known from a photograph showing a modest but distinguished, nearly square, brick, gable-front Federal-style building. The term Federal style is given to classicizing architecture of the Early Republic. These buildings were similar to colonial or Georgian structures in their massing and ornament, but often featured plainer surfaces with attenuated detail, including panels, tablets, and friezes.

Buildings of this period favored prominent round-arched windows, but also employed less ornamental rectangular apertures in secondary locations. Federal-style buildings mostly were simple shapes built of wood or brick, with gable-front roofs where the gable might be articulated as a classical pediment. This was the case in Richmond’s Beth Shalome: the synagogue had a facade with three arches, two windows, and one central entrance, all surmounted by a simple pediment. Arched windows can be seen on the left side. Presumably there were matching windows on the opposite side. The inside was probably one open hall, perhaps with women’s galleries on at least two sides.

The simple dignity of Richmond’s brick Beth Shalome, with its attractive proportions, round arched windows and

doors, and lack of exterior ornament, was in the tradition of the main body of Beth Elohim, Charleston’s first synagogue; and this type of simple and functional, but elegant, design—with only minor modifications—continued to appeal to Jewish congregations. Temple B’er Chayim in Cumberland, Maryland (1864), the former Shaare Tefilah Synagogue in New Orleans (1867), and the former home of Adas Israel in Washington, D.C. (1876), all are in this style.

Outside the Jewish sphere, this round ample open interior, well-lit by round-arched windows, was familiar in Protestant churches of all types. Derived from London churches, the form served High Church Anglicans (Episcopalians), but also the more modest Methodist and Baptist denominations, and could be used for Quaker meeting houses as well as synagogues. For Jews, the similarity of their synagogues to Protestant churches was due to both circumstance and intention. There were no Jewish architects in North America until the arrival of Leopold Eidlitz (1823–1908) from Prague (via Vienna) in 1843. Local architects and contractors were experienced in building for Protestant patrons and probably considered synagogues to be like churches. Jews, too, may have desired their religious buildings to resemble other houses of worship.

As we have seen, by the 1820s, North American Jews were receptive to architectural tastes of the new republic of which they were a part, just as they had adopted the popular styles of the colonial era. Thus, synagogues built in the first half of the 19th century, even those that maintained the Sephardic plan and liturgy, included Federal and Greek Revival details popular for public buildings of the day.

The popular Greek Revival style attempted a correct imitation of the ancient style, the result of the publication of measured drawings of ancient Greek buildings, but significant liberties were taken, such as a low interior dome at Beth Elohim in Charleston, hardly a feature of Greek design.

This new Greek style was used in many types of civic and religious structures in the second quarter of the 19th century. It was first used for an American synagogue in New York City, where Congregation Shearith Israel erected a new sanctuary (now demolished) on Crosby Street in 1834, and then again in the Bene Israel synagogue in Cincinnati in 1836. The Greek Revival found its most refined expression in Charleston, where KKBE built a new synagogue that resembled a Doric Greek Temple, albeit in the final design only one side of the building had exterior columns. Besides Beth Elohim, several contemporary churches also resemble Greek temples.

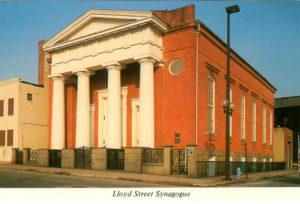

In Baltimore, Maryland, Congregation Nidche Yisroel, founded in 1830, held services for 15 years above a grocery until 1845,5 when the congregation, renamed Baltimore Hebrew, inaugurated its impressive new synagogue on Lloyd Street. Built in the Greek Revival style, it imitated Charleston’s second Beth Elohim, as well as other religious buildings erected in both cities in the late 1830s and early 1840s. The form and decoration of these Greek Revival synagogues recall ancient pagan temples more than the Jewish Temple of Jerusalem, and though both Charleston and Baltimore use Greek forms, they employ columns only on their facades, in a fashion closer to ancient Roman temple design than to Greek. More to the point, their synagogues signified their allegiance to the new civic architecture and identity of the United States.

Just as these Greek-style synagogues were being built, architects of religious buildings began to incorporate a multitude of historical fashions in their designs. Developments in Europe encouraged a revival of medieval architectural forms, especially the Romanesque and Gothic styles for church building. These were soon adopted for synagogues in Europe and America, too.

1 Saul Jacob Rubin, Third to None: The Saga of Savannah Jewry (Savannah, 1983), 43–44.

2 Solomon Nunes Carvalho (1815–1894), who had grown up in KKBE, offered the painting to the congregation “for what they thought it was worth.” The trustees bought it for $50, and it is now on view in the temple’s small museum. Carvalho and John Rubens Smith (1775–1849) both depicted the exterior, and their sketches show that a surrounding plank fence was replaced by a wrought iron one, an improvement noted in a congregational cash book in 1819. Dale Rosengarten, “Portrait of Two Painters: The Work of Theodore Sidney Moïse and Solomon Nunes Carvalho,” in By Dawn’s Early Light: Jewish Contributions to American Culture from the Nation’s Founding to the Civil War, ed. Adam Mendelsohn (Princeton: Princeton University Library, 2016), 139, n. 2.

3 Daniel K. Ackerman, “The 1794 Synagogue of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim of Charleston: Reconstructed and Reconsidered,” American Jewish History 93, no. 2 (June 2007), 169–171.

4 See Edward N. Calisch, The Light Burns On: Centennial Anniversary, Congregation Beth Ahabah (Richmond, Va.: Beth Ahabah, 1941).

5 Cyrus Adler and Henrietta Szold, “Baltimore,” in JewishEncyclopedia.com (the unedited full text of the 1906 Jewish Encylcopedia), http://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/2420-baltimore.