10.6 Columbus, Georgia

Temple Israel, 1617 Wildwood Avenue

Sigmund Braverman, architect, 1958

Colorama, Columbus, Georgia, publisher; no date

Like many older congregations, Temple Israel decided in the 1950s to leave its 19th-century building, relocate to the greener city periphery, and construct a synagogue in a pure modern style. In Columbus, Georgia, the Jewish Ladies Aid Society spurred the move. The women passed a resolution declaring the current temple inadequate and calling for a new house of worship. The post–World War II period was a time of growth for the congregation. Shortly after Temple Israel celebrated its centennial in 1955, the congregation purchased a new site and, in March 1957, broke ground for a sanctuary designed by Cleveland-based architect Sigmund Braverman of the firm Braverman & Halperin. The downtown building was sold and demolished in 1958, and the new temple was dedicated in March of that year. Between 1940 and 1982, the congregation more than doubled in size, growing from 80 families 182.

Braverman (1894–1960) was born in Austria-Hungary, came to America at the age of ten, and became one of the world’s most prolific synagogue architects. He is credited with more than 40 synagogues in the United States and Canada, in addition to many buildings in Cleveland, Ohio, where he was based. Besides Temple Israel in Columbus, Braverman designed several other synagogues in the South in 1950s, including Temple Oheb Shalom (1955) in Nashville, Tennessee, and Temple Adath Jeshurun (1958) in Louisville, Kentucky.

Braverman did not generally incorporate expressionist elements in his designs, as did the influential Eric Mendelsohn at B’nai Amoona in St. Louis. Braverman preferred a more rational and austere modernism, closer to the approach found in several pre–World War II synagogues in Germany, in what became known in this country as the International Style. Braverman worked with simple geometric shapes, mostly rectangles of different sizes, built from modest materials—especially brick and cast concrete—and arranged in a way to create a clear and meaningful progression from lesser to more important spaces.

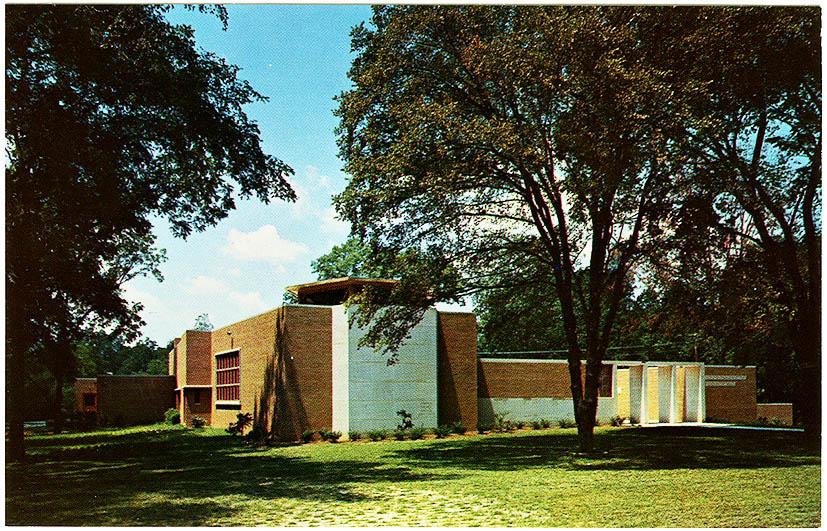

Temple Israel has an asymmetrical facade, a flat roof with shallow coping, and large expanses of windowless walls on various planes. An entrance courtyard with three unadorned connected openings faces the street. A brick wall to the right is inscribed with the passage from Isaiah 56:7 preferred by Reform congregations: “My House Shall be Called a House of Prayer for All Peoples.” To the left of the courtyard is the brick sanctuary, from which a central bay protrudes. This is clad in light-colored cast-concrete slabs, the same material used to outline the courtyard entrance. The prominent bay expresses the space of the Holy Ark within. Protruding arks have a long history in synagogue architecture, but in America, modernists like Braverman’s contemporary Percival Goodman made it a major facade element by turning the ark wall toward the street.

There are windows on the exposed flank of the sanctuary, and from a distance one can see a flat-roofed hexagonal lantern rising from the area in front of the ark. This has clerestory windows designed to add natural light above the bimah. We can compare this to the much more dramatic skylight employed a few years later by architect Sidney Eisenshtat at Temple Sinai in El Paso.

Like Goodman, Braverman leaves his exteriors mostly unadorned, but here he placed a relief sculpture on the exterior ark wall. It is not seen in this postcard, perhaps because the photo was taken before the structure was complete, but ultimately a large bronze relief Hebrew letter shin was installed, now the clear focus for any passer-by. Shin, which can stand for several important Hebrew words and concepts, brands the new building as “Jewish.” Otherwise, architecturally, it looks much like many suburban schools built in the 1950s to serve the Baby Boom generation.