10.2 Tulsa, Oklahoma

Temple Israel, 2004 E. 22nd Place

Percival Goodman, architect, 1955

Gough Photo Services, Tulsa, Oklahoma, publisher; no date; also on the back: “Genuine Natural Color made By Dexter Press, Inc., West Nyack, NY”

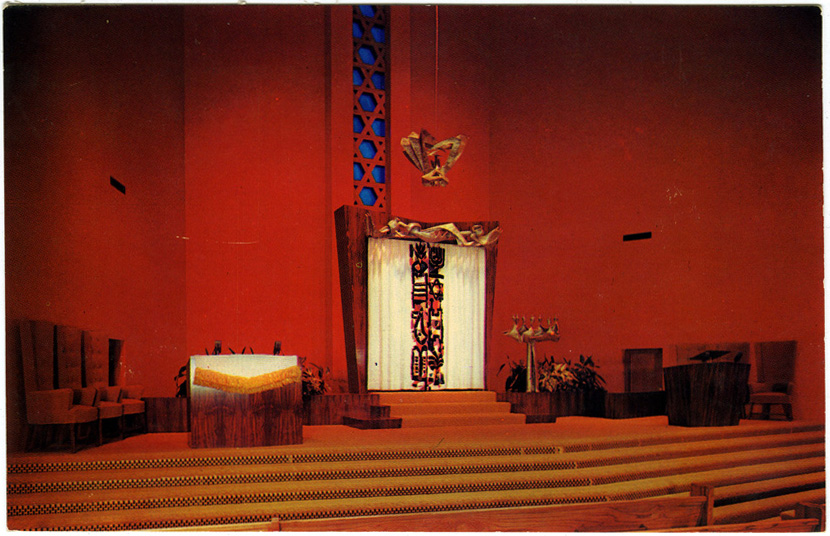

The theatrically lit interior of the sanctuary of Temple Israel, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, shown here, was a dramatic departure from traditional synagogue interiors. It is one of a series of impressive and expressive modern designs executed by architect Percival Goodman during the 1950s and 1960s (Goodman’s Beth Sholom in Miami is also in this exhibition) that combine shaped space, dramatic lighting, and a rich assemblage of modern religious art to create in the sanctuary a total immersive worship environment. Goodman was also a practical designer who provided functional—and more austere—educational, social, and administrative spaces.

The present building is the third for the congregation. The first building, erected in 1919, stood on the corner of 14th and Cheyenne streets and was replaced in 1932 with a new building on South Cheyenne. The present building opened in 1955.

The passage of time, and the many attempts to rival and surpass Goodman in novelty, have perhaps dulled our reaction to this place of worship. But a description by historian and critic Avram Kampf in his 1965 book shows how its originality could still elicit amazement a decade after its dedication. “The total effect of the bimah is stunning. The expressiveness of the shapes, materials, and colors makes the area unique, set apart, a sanctuary for the God of Israel. The historic element has become submerged in the esthetic element.”1

The synagogue’s front is dominated by massive twin pillars displaying the Ten Commandments, which represent the biblical Pillar of Fire and the Pillar of Cloud. Goodman engaged sculptor Seymour Lipton to produce three works of ceremonial art for the sanctuary’s bimah. Lipton was just one of several contemporary abstract sculptors (others were Ibram Lassaw and Herbert Ferber) whom Goodman introduced to synagogue decoration.

Kampf goes on to describe the interior of the sanctuary in vivid and evocative detail:

The area of the bimah is pronounced both in structure and color. The ceiling of the prayer hall declines gently from the sides to the middle in the manner of a tent, and comes to an abrupt stop above the steps of the bimah. The bimah itself forms the inside of a tower which rises to a great height. Its scarlet painted rear wall is divided through the middle by a vertical pattern of Stars of David designed in redwood against a dark-blue glass. The carpeting of the bimah is deep yellow, the ark structure redwood, the curtain white, with heavy black and polychrome decoration. The menorah, The Eternal light, and the sculpture which is placed along the top of the ark are made of nickel, silver and steel.2

For additional images see: https://synagogues-360.anumuseum.org.il/gallery/temple-israel-2/

1 Avram Kampf, Contemporary Synagogue Art, Developments in the United States, 1945–1965 (New York: Union of American Hebrew Congregations, 1966), 188.

2 Ibid.