8. New Forms in the New Century

Classicism wasn’t the only option for synagogue designers and their patrons but, following the popularity of the style nationally after the success of the Columbian exposition in 1893, many strong and innovative American design initiatives fell out of taste. The unique individual styles of American architectural masters such as H. H. Richardson, Frank Furness, Louis Sullivan, and others were mostly abandoned by establishment patrons, and most Jewish congregations followed suit, preferring acceptance over exceptionalism.

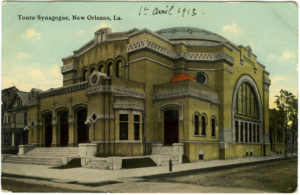

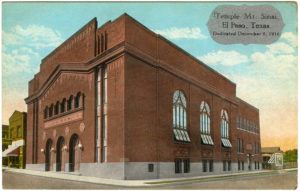

But there were a few variations and early experiments with forms that would become more common in the 1920s and afterward. In postcards, we see the notable and influential synagogue designs of Jewish architect Emile Weil for Touro Synagogue (1909) in New Orleans, Louisiana, which emulates domed synagogues popular in Central Europe; and Temple Mount Sinai (1916) in El Paso, Texas, a radical attempt to strip down a synagogue building to its geometric and structural fundamentals.

Touro’s sanctuary interior is defined by a large low dome that creates a blue oculus overhead, representing heaven. Stained glass windows surround the space, bathing the room in a soft light. The oak bimah is movable, allowing the rabbi to create a more intimate service when the 800-seat main sanctuary is not full, though more recently the congregation opted to build a smaller chapel as well.

Other domed alternatives to the classical temple were Ohev Sholom Temple (1925) in Huntington, West Virginia, and Temple Beth-El (1927) in San Antonio, Texas. These temples are indicative of two directions in 1920s synagogue design.

The nationally popular Byzantine style of the ’20s was susceptible to modern trends. Emphasizing simple geometric forms, qualities of building materials, and wall surface that tended to limit decoration to flat ornament, Byzantine synagogues could be sleek and cool, with smooth wall planes, sharp angles, and usually monochromatic sheathing in light stone or tile. The Art Deco style would further simplify these characteristics. The few Art Deco examples accentuated variants on the cube and sphere and utilized natural light as much as possible.

In Huntington’s Ohev Sholom, we see a variation of the Byzantine style that became fashionable in the 1920s, though here the structure still retains the massive block and square stair towers that recall the large Romanesque-style towered synagogues of the late 19th century.

In San Antonio, Temple Beth-El chose the then-popular domed, center-plan auditorium around which the rest of the layout was developed. Rather than choose a classical or Byzantine exterior, Beth-El applied a simple light-colored stucco on the exterior reminiscent of Southwest Spanish mission churches, and then added a rich layer of Spanish Baroque decoration to the facade. In this way, the building, which includes many modern amenities, was stylish and modern but still referenced local history and tastes.

The new Temple Mount Sinai (1916) in El Paso, Texas, designed by prominent local architect Henry Trost, went in an entirely different direction. Its form was a radical departure from its small predecessor (1899). Trost’s building looks more like a concert hall or theater than a synagogue. The congregation chose a non-traditional design and a decorative pattern of raised bricks and fanciful motifs under the cornice and the attic level roof line that are derived more from the Arts and Crafts Movement than from traditional Jewish sources or conventional medieval or classical architectural vocabularies. The playfulness of theater is more in evidence than the seriousness of religion.

The interesting buildings in this section are outliers, but they do point to greater variation in synagogue design in the decades to come.