5. Synagogue Towers

Some of the most striking postcard images in the Rosenthall Collection are of 19th-century synagogues with pairs of soaring facade towers. Towers were practical: side towers provided access via stairs to upper galleries. They were also symbolic: twin towers were linked to the two columns called Jachin and Boaz, said to have flanked the entrance to Solomon’s Temple. They were aesthetically pleasing, too, providing a bookend effect to frame the facade and emphasize the central entrance.

Towers came in many shapes and sizes. Sometimes they rose alone from the center of the building’s face and sometimes from the corner. Today only a handful of these towers survive, but at one time they were quite common. They announced a confident and prosperous Jewish community as clearly as any broadcast or billboard could. Christian churches had bell towers, and mosques had minarets from which the faithful were called to prayer. But for Jews, towers beckoned visually. As towers got taller, they had public relations value, locating the synagogue within streetscapes and skylines. Jews were proud of their freedom and did not hide from it. Grand synagogues, often with two-tower facades, were seen by many Christians as Jewish churches and respected as such by the public.

An early use of towers in the South was the two-tiered, faceted cupola poised over the main sanctuary of the first purpose-built synagogue of Charleston’s K.K. Beth Elohim, completed in 1794 (see Federal Style and Greek Revival). Later instances of towers over synagogue entrances can be seen in Columbus, Georgia; Nashville, Tennessee; Wheeling, West Virginia; Port Gibson, Mississippi; and Demopolis, Alabama, among others. The twin-tower trend for synagogues began in the United States in 1850, when German architect Alexander Saeltzer designed Anshe Chesed in New York, a large, Gothic-style synagogue, still standing. Its two-story facade is flanked by square and buttressed towers pierced by tall windows, culminating in concave pyramidal roofs. Significantly, in Orthodox synagogues, these towers housed stairways to galleries for women, who entered through the central portal but quickly turned to the side stair before reaching the main sanctuary door to the men’s space.1

Almost immediately towers became the norm in new construction. In 1851, New York’s Congregation B’nai Jeshurun dedicated a Gothic-style two-tower building on Green Street, and, in 1853, the Romanesque-style Rodeph Shalom was completed on Clinton Street. The latter included flanking square towers, but these hardly rose above the lowest part of the front gable roof.

Thus, two-towered synagogue facades were not unknown before the Civil War, but the form did not spread until the period of expansive synagogue construction that began after the war and lasted through the 1890s.

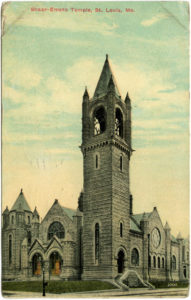

Shaare Emeth of St. Louis (1867) was among the first southern synagogues built with two prominent towers flanking the facade. The inspiration for the arrangement was not in New York but in Cincinnati, where Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise’s Plum Street Temple, dedicated in 1866, combined Moorish and Gothic elements, and in San Francisco, where Temple Emanu-El on Sutter Street opened that year. Temple Emanuel in New York, contemporary with Shaare Emeth, had two towers surmounted by open pavilions.

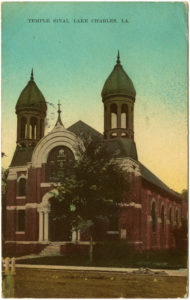

The biggest and boldest facade towers in the South belonged to Temple Sinai in New Orleans (1872). Similarly dominating towers were built in Lake Charles, Louisiana, as late as 1904 (the original onion domes were blown off during the storm of 1918). A more modest version could be seen at Moorish-style Congregation Adath Yeshurun (1908) in Houston, Texas, where small towers culminated in two open pavilions built onto the roof’s surrounding parapet wall. A similar arrangement had existed at the still-extant synagogue in Port Gibson, Mississippi (1892), before the side towers were removed. Yet another instance is the first building of Temple Emanuel (1901) in Beaumont, Texas. Among other examples across the Lone Star State, the wood-frame former Beth El in Corsicana, in 2021 a community center, is the only survivor.

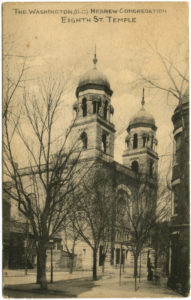

Substantial towers appeared in the 1890s in the former Baltimore Hebrew (1891) and Oheb Shalom (1892) in Baltimore; the former Washington Hebrew in Washington, D.C.; and Lake Charles, Louisiana, where Temple Sinai continues to serve the congregation, though the towers are long gone. These were Reform congregations, but Orthodox congregations also adopted the two-tower design at the turn of the 20th century. The Orthodox Talmud Torah (1905) in Washington, D.C., resembled Washington Hebrew. The two-towered Jacksonville, Florida, B’nai Israel (in 2021 the Jacksonville Jewish Center), was built for an Orthodox congregation in 1909.

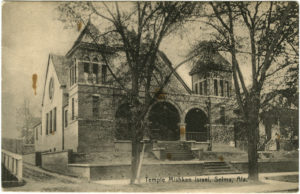

In the 20th century, paired towers got shorter and blockier, as in Touro Synagogue in New Orleans, Louisiana; Congregation Mishkan Israel in Selma, Alabama; and Temple B’nai Israel in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. This configuration became a regular feature of many freestanding Byzantine-inspired synagogues built in the 1920s.

A new type of synagogue—broader and lower—emerged in the first years of the century. Block-like buildings, the facades were often flanked by a pair of squat towers, sometimes capped by small domes or cupolas, often flat-topped. A good example of this is the former Children of Israel (1916) in Memphis, Tennessee. The domed structure still stands, but was sold by the congregation to the Mid-America Baptist Theological Seminary in 1976, and, by 2021, was part of the Memphis Academy of Science and Engineering Charter School. A less pronounced use of corner towers, in this case dwarfed by the central mass of the building, is in Ohev Sholom Temple in Huntington, West Virginia, built in 1923.

By the end of the 1920s, however, the age of the tower had passed.

1 The Great Metropolis: or New-York Almanac for 1850, published by H. Wilson, describes this Gothic synagogue, but hardly mentions its impressive towers: “This edifice is in the German Gothic style of architecture, and derives an interest aside from the elegance of its exterior, from its being of a style of architecture entirely new in this city, but of which frequent and noble specimens are met with in the country from which it had received its denomination. . . . There are galleries (the entrances to which are through the towers) which are devoted exclusively to the female portion of the congregation who are in all Jewish congregations separated from the males.”

Baltimore, MD ~ Baltimore Hebrew Congregation/Madison Avenue Temple (1891)

Baltimore, MD ~ Congregation Oheb Shalom/Eutaw Place Temple (1892)

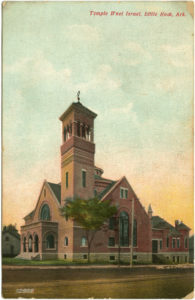

Little Rock, AR ~ Temple B’nai Israel (1897)

St. Louis, MO ~ Congregation Shaare Emeth (1897)

Washington, D.C. ~ Washington Hebrew Congregation/8th Street Temple (1898)

Selma, AL ~ Congregation Mishkan Israel (1900)

Pine Bluff, AR ~ Congregation Anshe Emeth (1902)

Lake Charles, LA ~ Temple Sinai (1904)

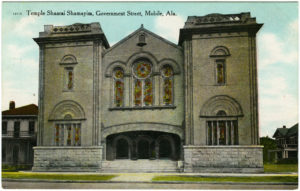

Mobile, AL ~ Congregation Sha’arai Shomayim (1907)

Jacksonville, FL ~ Congregation B’nai Israel (1909)