2. Gothic Revival

The common belief that American Jews eschewed the Gothic style for the construction of synagogues because of its association with church architecture is contradicted by the facts. Many examples of Gothic synagogues were erected across the continent in the mid-19th century by Jewish congregations of Central European origin. Beginning around 1850, some impressive urban synagogues were built entirely in Gothic style, and many more incorporated Gothic elements as part of their design. Architects of southern synagogues quickly embraced the national trend, and, in the second half of the century, synagogues around the region were commonly built with Gothic features or re-purposed from former Gothic-style churches.

Across America, the popularity of Gothic architecture for residential and religious buildings marked a shift away from Greek Revival, with its strong historical and civic associations, toward the more decorative, whimsical, and even mystical Gothic. Vestiges of the style were used in synagogue design well into the 1890s, reflecting the general rise of the Romantic Movement, which created a propensity for neo-medieval styles. From England came the infiltration into American religious circles of the teaching and architectural taste of the so-called Oxford Movement, through the buildings of A. W. N. Pugin, which in turn influenced the architecture of Episcopalian and Presbyterian churches.1

The adoption of Gothic architecture in America was stimulated also by German-born architects who were familiar with the style from Europe. For several decades the Gothic style was fashionable among German-speaking Jewish populations. Since German-speaking Jews often hired German architects, it may be that they also influenced Jewish stylistic preferences. There were Gothic precedents for Jews, too. Medieval Gothic synagogues could still be found in Europe, notably Prague’s revered 13th-century Altneushul (Old-New Synagogue), built of stone with intricate cross vaults, pointed windows, and external buttresses. In the 19th century, the Altneushul was probably the most illustrated synagogue in the world, often visited by observant Jews, Romantic-period literati, curious tourists, and scholarly historians.

An early instance of Gothic detailing on an American synagogue was at Cincinnati’s B’nai Yeshurun, built in 1848. This plain three-story brick building was described as “in the Gothic style” because of two pointed arches over its side doors and the pointed stringcourse elements applied to its buttresses.

In New York, the still-extant synagogue at 172 Norfolk Street (today housing the Angel Orensanz Foundation) was built in 1850 as Anshe Chesed. Designed by the German-born Alexander Saeltzer, it reflects the influence of Germany’s Cologne Cathedral, where construction was renewed in 1842. The synagogue’s facade originally had two impressive side towers like those of the cathedral, and it ushered in two important European innovations in American synagogue design: Gothic arches and vaults, as well as two-tower facades. Anshe Chesed was followed in 1851 by a similar second home for New York’s Congregation B’nai Jeshurun on Green Street.

In California, the Gothic style was used for synagogues as early as 1850, when two Jewish congregations were organized in San Francisco. Sherith Israel was “Anglo-Polish,” and Emanu-El followed the “German” minhag (liturgy). Both congregations dedicated Gothic-style synagogues in 1854.2 They were built of brick with buttresses, pinnacles, pointed windows, and applied molded arches. Nearly two decades later the style was still popular in the West, as evidenced by the impressive Gothic building Congregation B’nai B’rith erected in Los Angeles in 1873.

Jewish communities on the west coast seemed especially enamored of the style; it gained new impetus in 1866 with the completion of San Francisco’s new Temple Emanu-El on Sutter Street, an enormous two-tower cathedral-like structure, with bronze-plated domes visible from afar. Even more than New York’s Anshe Chesed, this tall building was inspired by the Cologne Cathedral. Also renewing interest in the style were other Gothic cathedrals, such as the one in Milan, Italy, which was finished in the 19th century.

It did not take long for the Gothic style to reach the South. During the 19th century, variations of both Gothic and Romanesque styles, sometimes mixed with other historicist styles, were regularly used throughout the region. In the late 1860s, when Reform congregations in Cincinnati and New York City adopted the distinctly different Moorish style for synagogue design, this, too, was often mixed with Gothic elements. Soon after, B’nai Israel in Galveston, Texas, built in 1870, reportedly presented “a handsome exterior, in which the perpendicular Gothic style prevails.”3

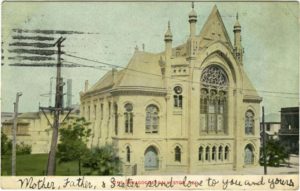

Adaptation of the Gothic style could take many forms, and often builders selected only a few telling details, such as pointed arches; tall narrow windows, often in multi-partite combinations; applied exterior buttresses; stained glass windows; trefoil decorative patterns; or an assortment of pinnacles and towers. Interior cross vaults were sometimes used—almost always as part of plaster ceilings. Any of these elements could be enough, however, to allow a new synagogue to “fit in” with other religious buildings in a town, or even on a single street.

The most fully developed and unabashedly Gothic southern synagogue is Mickve Israel (1878) in Savannah. B’nai Israel in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, had lovely Gothic windows and doorways, which probably dated from structure’s original incarnation as a Christian Brothers School, built sometime before 1876. Temple B’nai Israel (1887) in Columbus, Georgia, included Gothic elements, especially its prominent exterior buttresses. The eclectic North Carolina synagogues Ohev Sholom (1886) in Goldsboro and Temple Emanuel (1892) in Statesville both employed exterior buttresses, which gave their otherwise round-arched buildings a decidedly Gothic look. Ohev Sholom in Huntington, West Virginia, employed the Gothic style as late as 1892, when the congregation built its first home at Fifth Avenue and Tenth Street.

Simple wood-frame buildings also could sport Gothic elements, as in the Orthodox B’nai Abraham shul (Yiddish for synagogue) of Brenham, Texas, built in 1893, with pointed window frames.4 The nearby Brenham Presbyterian Church was built in a similar though grander Gothic style. In addition, many congregations occupied former churches that had been built in the Gothic style. These include Temple Brith Sholom, in Louisville, Kentucky, which moved into a Gothic-style former Presbyterian Church in 1903 and remained there until 1950; and Ahavath Sholom Congregation in Bluefield, West Virginia, which occupied the former Scott Street Presbyterian Church from 1907 to 1941.5

1 On the Gothic Revival in America, see Phoebe B. Stanton, The Gothic Revival and American Church Architecture: An Episode in Taste, 1840–1856 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1968). On the first American Gothic-style synagogues, see Rachel Wischnitzer, Synagogue Architecture in the United States: History and Interpretation (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1955), 50–57.

2 Rachel Wischnitzer, Synagogue Architecture in the United States: History and Interpretation (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1955), 50–57.

3 “The New Synagogue,” Galveston News, Tuesday, May 25, 1871.

4 B’nai Abraham was moved to the Dell campus in Austin, Texas, in 2015.

5 Illustrated in Julian H. Preisler, Jewish West Virginia (Arcadia Publishing, 2010), 14.