7.5 Monroe, Louisiana

B’nai Israel (Bene Israel), Jackson Street, corner of Jackson and Oak streets

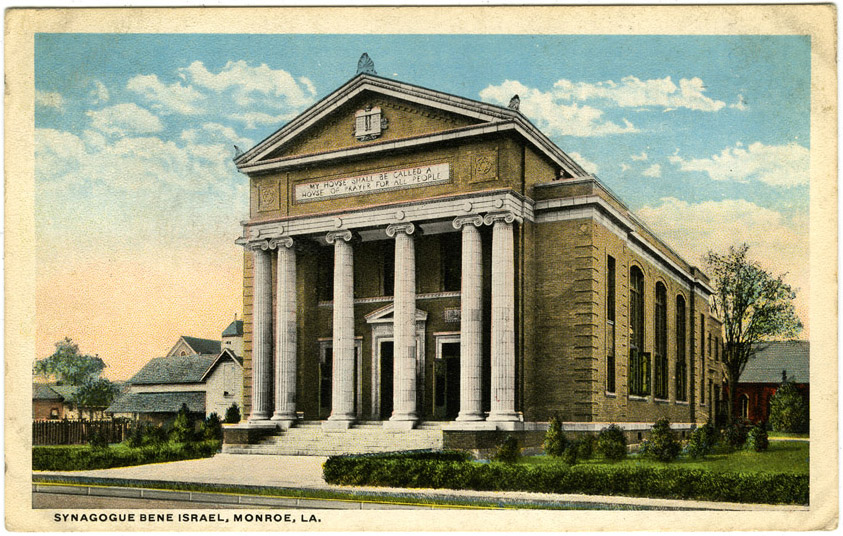

Stevens and Nelson, architects; Frank Masling, builder, 1917

Bailey’s 5-10 and 25c Store, Monroe, Louisiana, publisher; no date; also on the back: “C. T. American Art”

The Jewish community of Monroe dates from 1861. From then until 1870, worshipers gathered in various homes. The Reform congregation B’nai Israel (Sons of Israel) was incorporated in 1868. The next year they bought land and built a brick synagogue. Thirty-five years later the congregation was ready to build again.

In 1914, Col. W. L. Stevens of New Orleans was chosen as architect for a grand new temple. He and Sam Kaplan, head of the building committee, visited “a number of the finest Jewish houses of worship in the North”1 to get ideas for the new building. Steven’s ultimate design was confident and robust, with a temple-style front porch consisting of six tall fluted Ionic columns supporting an attic and pediment in front of three rectangular doorways giving entrance to the building.

The structure was probably built of steel and clad in brick and terracotta. It was not completed until 1917, and that may have been because of material or labor shortages during World War I. The postcard shows the columns constructed of drums, which may have been hollow tile surrounding a steel support that helped carry the weight of the roof. The space between the central two columns was wider, providing an appropriately ample and inviting entrance.

On the attic, a wide panel proclaimed, “My House Shall Be Called a House of Prayer for All People,” the egalitarian welcome expression common to most Reform temples of the time. Flanking the inscription were two brick panels containing Jewish stars. Despite the adoption of the Magen David (Star of David) as the symbol of Zionism, in this instance the symbols probably were meant to connote Judaism in a more general way—as counter symbols to the Christian cross. Reform Judaism firmly rejected Zionism at this time in favor of a fervent American nationalism and the belief that the United States was the ideal home of Jews.

By the second decade of the 20th century, the classical style chosen for the new building was typical for Reform temples across the South. It represented, among other things, full engagement of the Jewish congregation in the civic and patriotic identity of the larger community. This spirit of acculturation and integration was expressed in the words of the Jewish Ledger, found in the time capsule of the 1917 building: “Jew and Gentile labored side by side for the good and welfare of all its people free from cant and prejudice.”2

In 1961, the congregation moved to a new modern-style building on Orell Place; eight years later, the Jackson Street temple was demolished.

1 “Preparing Plan for Temple,” Monroe News Star, February 6, 1914.

2 Cited without date in “Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities – Monroe, Louisiana,” Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life, http://www.isjl.org/louisiana-monroe-encyclopedia.html.