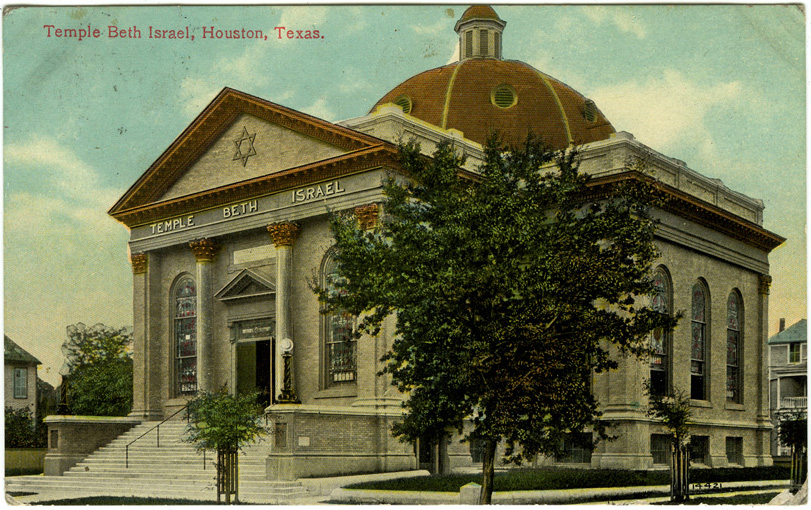

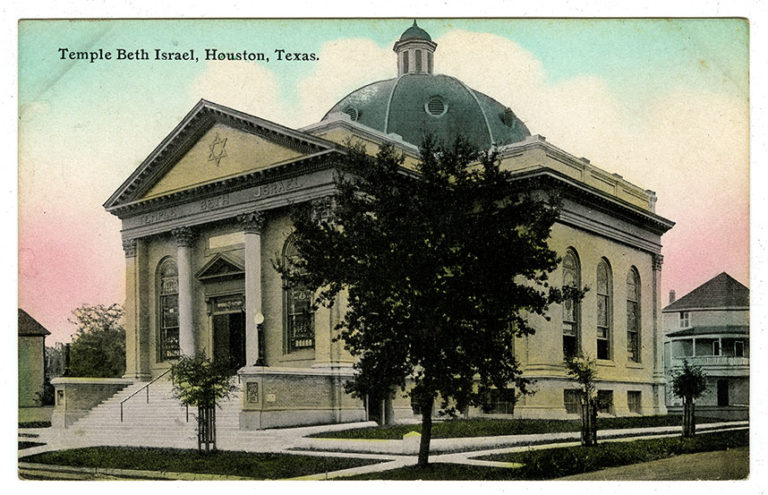

6.13 Houston, Texas

Beth Israel, Crawford Street at Lamar Street

C. H. Page. Jr., architect, 1908

Publisher and publication date unknown, but postmarked June 18, 1911

In June 1870, Beth Israel (House of Israel) announced plans to build an “Israelitish Church” on Franklin Avenue. According to the local newspaper, a thousand people took part in the celebration and “all classes of Houstonians have taken a warm interest in [the synagogue’s] inauguration.”1 By 1908, the congregation had outgrown this Romanesque-style synagogue and moved to Lamar and Crawford streets (now Discovery Green, a public park), where it built a new classical-style temple, shown here.

The building was a mature expression of the new classical ideal, with all the key elements: an axial approach via a grand stairway entrance, through a colonnade, under a prominent pediment, into a vestibule from where stairs led to the gallery above. Doors opened into the sanctuary, surmounted by an ample dome. An earlier design of 1905, published in the Houston Post, was much more elaborate with a high central dome and four corner open turrets, perhaps inspired by Eutaw Place Temple in Baltimore, or recent architecture at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair.

The completion of the synagogue coincided with the publication of the first issue of the Jewish Herald (September 24, 1908), which devoted much of the publication to this new synagogue and the nearly contemporary new building for the Orthodox congregation Adath Yeshurun. The paper declared “the temple is one of the most notable pieces of religious architecture in Houston.” The lengthy article described the synagogue’s classicism, though inexpertly uses the term Romanesque: “the Romanesque style, with Romanesque arches and a dome, and its floor plan describes a Greek cross. . . . The great, solid and dignified front of the building impresses one with strength and solidity at first glance. . . .”

In style, the building is a mix of classical (the portico) and Renaissance (the dome) that harks back to ancient models via the architecture of Alberti, Palladio, and Thomas Jefferson. As other examples in the section demonstrate (Natchez, Meridian, and Greenville), this combination of forms was popular at the time for synagogues, as well for some churches, civic buildings, and banks.

The Jewish Herald lavished praise on the interior, remarking “Everything here is finished in white, with the woodwork of walnut. The arched roof and trusses are of stamped steel, and the majestic rise of the dome adds grace and dignity to the interior, besides adding to its acoustic value. . . . The platform is of walnut, the altar is of walnut and behind the altar is the ark, also of walnut. . . . The front of the ark presents a highly decorative effect in scroll work and symbolic carving, all in walnut, backed with crimson velvet. A choir loft over the ark contained a full-size pipe organ.”2

The Jewish Herald extolled “the light that “filters through the stained glass” and “the red light that burns perpetually before the altar . . . and the symbolic carvings and tracery work of the ark in which rests the Torah, and the altar itself, with its velvet hangings and great embroidery piece representing the shield of David. . . .” It is noteworthy that though the article is printed in a Jewish publication, the author mistakenly calls the ark an “altar.” This linguistic slip is an indication of how much the Reform temple was often understood to be a “Israelitish Church.”

Rabbi Harry Barnston, who as the young rabbi of the congregation helped spearhead the building effort, wrote an account of the construction, and provided additional information. The total cost of the temple was about $50,000. There were ten stained glass windows fabricated by the Texas Art Glass Company, “five of which are memorial windows, exhibiting scenes from Israelitish History and Jewish Ceremonial.”3 The Jewish Herald account noted that:

[In] each window appears some device or design typical of Hebrew history or of Jewish ceremonial. There is the six-pointed star, the two hands raised in blessing, the seven-branched candlestick, the two tables [sic] of the law, the sacred scrolls, and various other representations typical of Israel.4

When Beth Israel moved to its next home in 1925, the building was sold to the newly founded Conservative Beth El Congregation, from which we have photos of the ark and bimah.

The building was demolished in the 1970s, and, as of 2021, the site was part of Discovery Green, a 12-acre urban park. Four of its 15-foot-high stained glass windows were rescued and are now installed in the Sherwin Miller Museum of Jewish Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

1 “City Item,” Houston Daily Telegraph, June 17, 1870, quoted in Anne Nathan Cohen, The Centenary History, Congregation Beth Israel of Houston, Texas, 1854–1954 (Houston: Congregation Beth Israel, 1954), 19.

2 All quotes from “Temple Beth Israel is Now Completed,” Jewish Herald, September 24, 1908.

3 Harry Barnston, “History of the Jews of Houston,” paper, quoted in Anne Nathan. The Centenary History, Congregation Beth Israel of Houston, Texas, 1854–1954 (Houston: n.p., 1954), 36.

4 “Temple Beth Israel is Now Completed,” Jewish Herald, September 24, 1908.