2.4 Savannah, Georgia

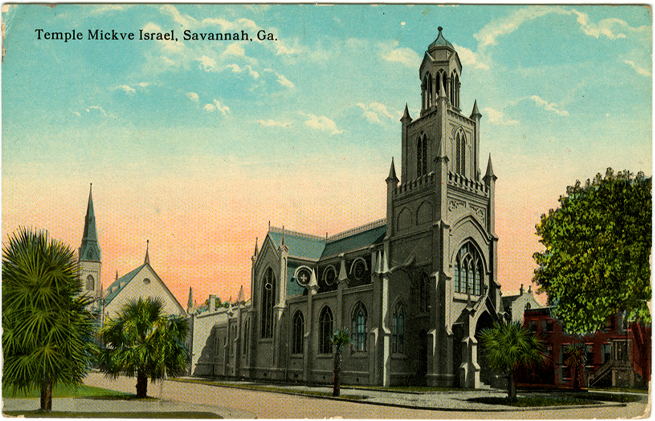

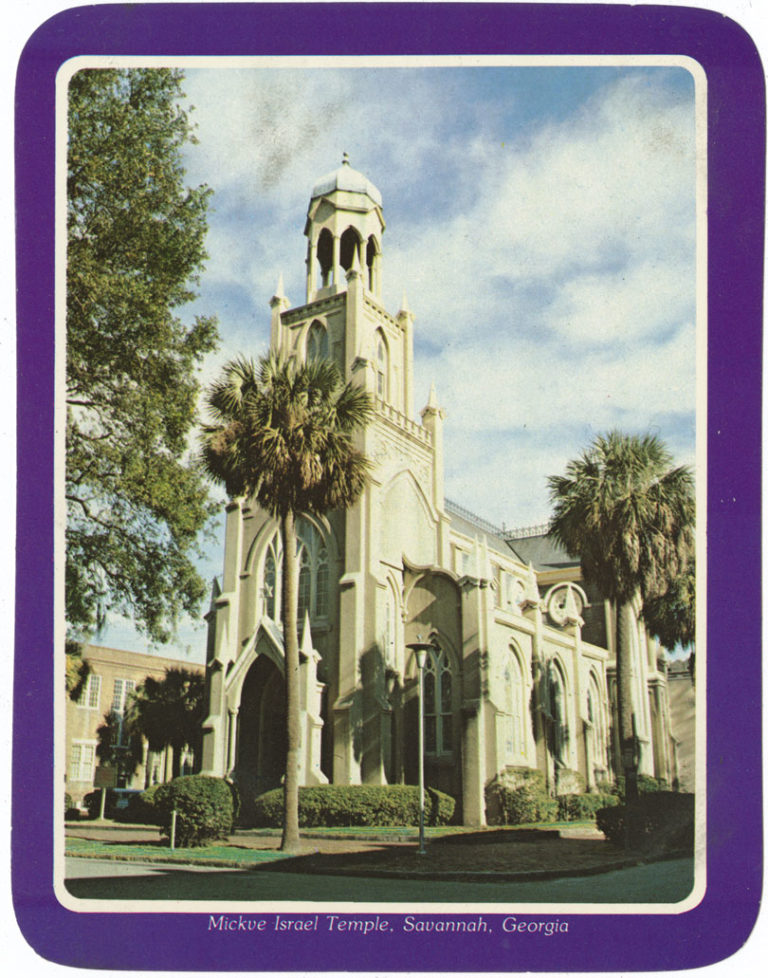

Temple Mickve Israel, 20 E. Gordon Street

Henry G. Harrison, architect, 1878

Silver’s 5 & 10 Cent Store, Savannah, Georgia, publisher; no date

Temple Mickve Israel (Hope of Israel) on Monterey Square in Savannah is one of America’s best known and most unusual synagogues. Designed by New York architect Henry G. Harrison, the Gothic-style building reflects the fashionable architecture of the Victorian era. The impressive new edifice physically established Savannah’s Jews as an integral part of the local religious landscape.

Jews first arrived in Savannah in 1733. The Jewish population ebbed and flowed through the 18th century; Mickve Israel dedicated its first synagogue only in 1820. With the substantial Central European immigration to America in the 1840s and 1850s came a significant influx of Jews. By 1874, the small synagogue on Liberty Street and Perry Lane was no longer sufficient. On March 1, 1876, the cornerstone was laid for a grand building on Monterey Square, and the sanctuary was consecrated on April 11, 1878.

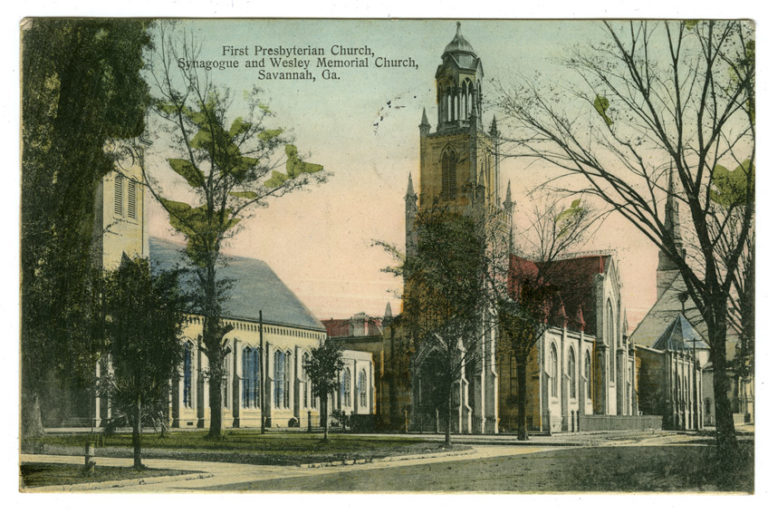

The new synagogue developed the popular Gothic style in synagogue architecture into a more traditional Christian-inspired design. The church-like appearance was intentional: to link in dignity and beauty the history of Mickve Israel to the many similarly sited houses of worship built in a variety of mostly English-inspired church styles. Nearby on the same square once stood a Gothic Revival Presbyterian church, which was destroyed by fire in 1929.

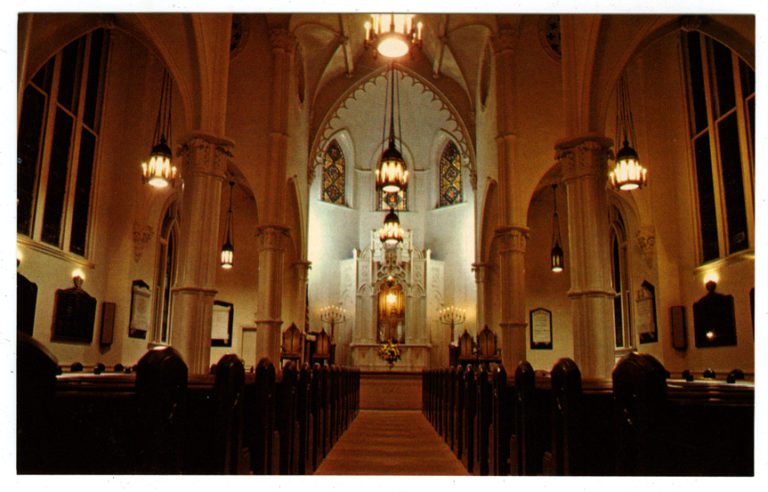

The synagogue appropriated Christian forms and details, such as a central tower, Gothic windows, turrets, finials, and stained glass. Many of these elements were familiar in other period synagogues, but when integrated in a cruciform plan at Mickve Israel, the collection of parts evoked a closer association with medieval Christian tradition than did other synagogues.

Again, the correlation was intentional. The congregation clearly wanted an English Gothic synagogue, and few architects were as immersed in the Ecclesiastical Gothic Revival architecture of England as Harrison. His best-known works were churches, including the Cathedral of the Incarnation in Garden City, New York, erected from 1877 to 1883, just when Mickve Israel was being designed and built. Harrison and his Jewish Reform patrons must have been aware of the newly erected Temple Emanuel (1868) and Central Synagogue (1872) in New York. Perhaps as a concession to the Jewish identity of the new building, Harrison included an unusual top level of the tower. Instead of rising to a pointed pinnacle or spire as might be expected, the tower is topped with an open gazebo-shaped belvedere surmounted by an almost Islamic-inspired cupola.

In 1875, the full congregation unanimously approved the Gothic sanctuary plan. Later the building committee accompanied Harrison to inspect local churches. Architectural historian Stephen Moffson writes: “In shedding virtually all Jewish symbolism in favor of Christian architectural forms, Mickve Israel removed visual distinctions between itself and the gentile community.”1 The Christian community responded approvingly in newspaper articles of the “impressive consecration rites” attended by local political leaders and Christian clergy.2 A letter from a Pennsylvania woman to the congregation’s president expressed this sentiment, which today seems quite unsettling:

You are the first Israelites I have ever heard of to build a church in the shape of a cross, the symbol of the Holy Trinity . . . the symbol of Him who is despised by so many of your people. . . . [W]hat a comfort to know you have taken this step to enter our fold. . . . Doubtless, you have had to overcome great perplexities before your people consented to have a church built so ultra-Christian in form. (Mary M. Chisolm to President of the Israelite Church, April 8, 1876, Mickve Israel Collection, Savannah Jewish Archives, Savannah, Georgia).3

1 Steven H. Moffson, “Identity and Assimilation in Synagogue Architecture in Georgia, 1870–1920,” Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture 9 (2003): 155, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3514431.

2 Savannah Morning News, April 12, 1878, p. 3, cols. 4–6. Quoted at length in Rubin, 183.

3 Steven H. Moffson, “Identity and Assimilation in Synagogue Architecture in Georgia, 1870–1920,” Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture 9 (2003): 155, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3514431.