3. Romanesque and Round-Arched Style

The Romanesque style, like the Gothic, became immensely popular in America in the 1840s and 1850s. However, the Romanesque was adapted to more types of buildings, including institutional, commercial, and religious structures. Many of its features—such as round arches for doors, windows, and decorative corbel tables at the tops of walls—became part of the 19th-century American vernacular.

The style was first taken up by recent Jewish immigrants from Germany, Bohemia, and Alsace, the Rhineland region that shared German and French cultural and political history and was the homeland of many Jewish immigrants who settled in the South. In Central Europe, the round-arched style (German: Rundbogenstil) was already familiar for synagogue building. The only surviving, medieval synagogue built in the Romanesque style was the small, freestanding, 12th-century synagogue of Worms, Germany, a venerated structure among both religious and secular Jews striving to assert a Jewish national identity.

Still, it is more likely that 19th-century American synagogue builders were directly influenced by recent synagogues in France, Germany, and elsewhere than by medieval models. The best known of these was the synagogue in Kassel, Germany, erected in 1839. This was the first synagogue on which a trained Jewish architect, Albrecht Rosengarten, is known to have worked. He later wrote a widely used manual on architectural styles that was also translated into English.

In America the Romanesque style appeared first in the Eagle Street synagogue of Congregation Anshe Chesed (1846), Cleveland, Ohio, and became popular in the decade before the Civil War in other large cities. Prominent examples include the Wooster Street synagogue of Congregation Shaaray Tefila (1847), New York City, and Rodeph Shalom (1853) on Clinton Street, New York City. The style was adopted by the Sephardic congregation Mikveh Israel (1860), Philadelphia, and variations caught on in the South in the decades after the war.

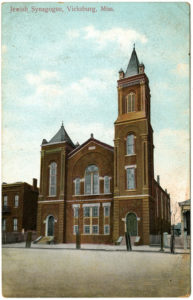

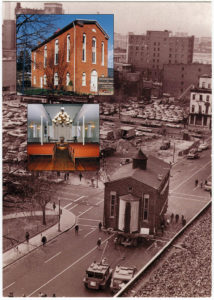

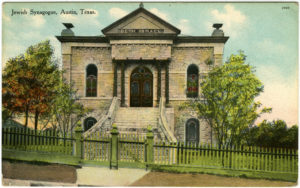

Round-arched styles used for simple buildings could create more monumental structures, such as Temple Sinai in New Orleans, a large two-tower synagogue, in 1872. Congregation Anshe Chesed (1870) in Vicksburg, Mississippi, and Adas Israel (1876), built in Washington, D.C., used round arches more in the Federal style of the first Beth Elohim in Charleston. Congregation B’nai Israel (1884) in Austin, Texas, employed a more Renaissance-inflected round-arched style, and included alternating-sized voissoirs for its arches, porch columns, and a classically inspired pediment. All these synagogues, however, shared an essential rectilinear plan centered on the long axis, creating a box-like sanctuary.

Much of Romanesque architectural decoration was created by adjusting the design of structural bricks and stones to form repetitive patterns. Straightforward geometric massing, symmetrical and axial arrangements, and repetitive wall and window patterns made the Romanesque style easy to build. It encouraged simple articulation of walls, doors, windows, roofs, and other building elements, and did not require excess work or expense to add ornate architectural details and decorative touches—though in New Orleans the towers received a lot of attention, and probably building funds, too.

Though medieval Romanesque churches often had multi-aisle interiors, in America the style was also widely adapted for hall-type plans where the sanctuary was a single space beneath a wooden roof or plaster vaults, with seating on either side of a central aisle. Some Romanesque-style synagogues, however, included traditional interior galleries that ran the length of the sanctuary, and this arrangement did create tri-partite interior divisions resembling medieval aisles. This was more a practical accommodation than a historical reference. In the South, most new synagogues in the mid-to-late 19th century were Reform temples, and these had no women’s galleries, but did have choir and organ lofts, which were usually placed on the short walls above the entrance and above the ark. Congregants enjoyed the full sanctuary height, though sometimes the hall itself was set high above a half basement, or even on the second floor.

The Romanesque style fit nicely with other prevalent building styles in America. American builders were not stylistic purists and frequently mixed elements from one style with another.

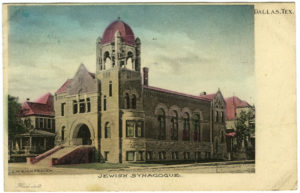

By the 1890s, many of the congregations formed mid-century built new and bigger structures—some replacing older buildings and others building anew in a new neighborhood. This was the case in Baltimore, St. Louis, and Dallas; congregations followed wealthy members to new neighborhoods where they often chose to build in a variation of the still-popular Richardsonian Romanesque style, a robust variant of the Romanesque that employed rusticated masonry and a more varied building shape, often including a corner tower.

Vicksburg, MS ~ Congregation Anshe Chesed (1870)

New Orleans, LA ~ Temple Sinai (1872)

Washington, D.C. ~ Adas Israel (1876)

Austin, TX ~ Beth Israel

St. Louis, MO ~ Temple Israel (1888)

Demopolis, AL ~ Congregation B’nai Jeshurun (1893)

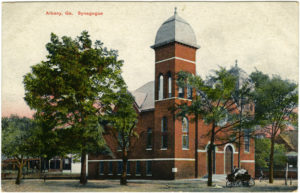

Albany, GA ~ Congregation B’nai Israel (1896)